Isaac Bashevis-Singer: A Literary Journey Through Time

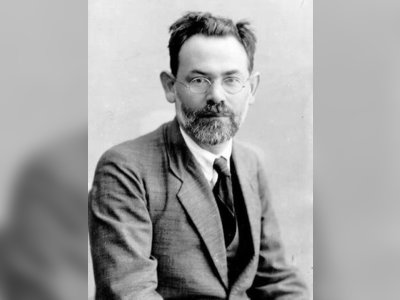

Isaac Bashevis-Singer, also known as יצחק בשביס-זינגר in Yiddish, was born on November 21, 1902 (or possibly July 14, 1904) in Radzymin, Poland, and passed away on July 24, 1991, in Miami, Florida. He stands among the greatest Yiddish writers of all time and is recognized as a distinguished Polish-Jewish author who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978. His life was a fascinating odyssey that spanned two continents, Poland and the United States.

Early Life and Background

Isaac Singer was born in the early 20th century in Radzymin, a small village in Poland. He grew up on Krokmalna Street 10, a Jewish neighborhood in Warsaw, the capital of Poland. While he officially claimed July 14, 1904, as his birthdate, it is believed that he was born earlier, either on November 21, 1902, or November 11, 1903.

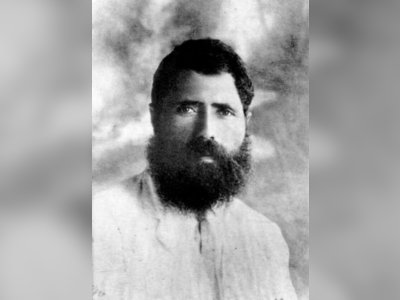

His parents were devoutly religious: his father, Rabbi Pinchas Menachem, served as a rabbi and head of a yeshiva, and his mother, Bat Sheva, was the daughter of Rabbi Jacob Mordechai Zylberman. However, Isaac's siblings, Israel Joshua Singer and Esther Kreitman, eventually abandoned their faith and became Yiddish writers in their own right.

Isaac moved to Warsaw with his parents at the age of six, but due to severe poverty, he left with his mother for Bilgoraj, her hometown, at the age of 16. Bilgoraj was where Bat Sheva's father had served as a rabbi. Until the age of 12, he had little exposure to secular literature, but during his early years in Warsaw, his religious beliefs waned, and he developed an interest in science, philosophy, and world literature.

At the age of 20, Isaac returned to Warsaw at the invitation of his brother, the writer Israel Joshua Singer, who encouraged him to cut his sidelocks and adopt modern clothing. He initially wrote his early stories in Hebrew but soon transitioned to Yiddish, the language spoken by the majority of Eastern European and American Jews at the time. He also began working as a proofreader for a literary newspaper and translated books from German to Yiddish.

In 1923, thanks to his brother, Isaac joined the Jewish Writers and Journalists Association located at 13 Tłomackie Street in Warsaw, a neighborhood known as "Hueln" (The Nook). During this period, a diverse group of Yiddish writers and activists, including Yiddishists, Zionists, revisionists, and territorialists, gathered there.

This association became a significant part of Isaac Singer's life, and he remained connected to it. He formed close friendships with fellow writers such as Aaron Zeitlin and Y.Y. Trunk. In 1932, Singer joined Zeitlin as an editor for the Yiddish literary magazine "Globus." He was influenced by Trunk's secular worldview.

Jente Hadda, Singer's biographer, adds that he also attempted to engage in romantic relationships with the women he met at the association. He believed that such interactions were necessary for him as a modern Yiddish writer. However, he often felt awkward and anxious, fearing that these women viewed him with condescending amusement.

In Warsaw, Singer worked as an editor for a literary magazine and translated German books into Yiddish. One notable translation was Thomas Mann's "Der Zauberberg" ("The Magic Mountain"). In 1935, his older brother emigrated to America, and Isaac followed suit, working with his brother at the Yiddish newspaper "Forverts."

Adopting the pen name "Bashevis," he honored his mother's name, Bat Sheva, who perished in the Holocaust. He also used other pen names such as Warszawski and D. Segal. His works were translated into numerous languages, and several of them were adapted into plays and films, including "The Slave," "Enemies: A Love Story," and "Yentl," which was based on his story "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy." For many years, Isaac Bashevis-Singer lived in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York City.

Isaac Bashevis-Singer passed away in Miami, Florida, on July 24, 1991, and was buried in a small cemetery in Northern New Jersey. A street in Tel Aviv's Gush Hagadol neighborhood was named after him in January 2008, following his son Israel Zamir's efforts to commemorate his father's legacy.

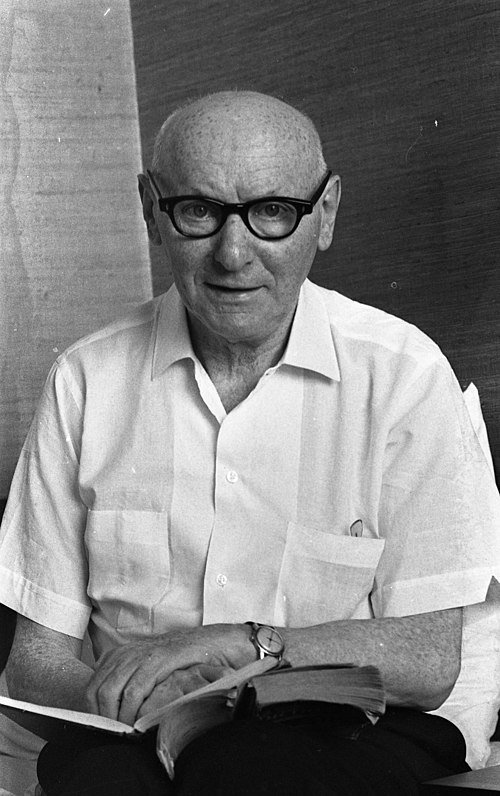

Literary Legacy

Isaac Bashevis-Singer declared that his ultimate goal was, and always would be, to tell a story. In his conversation with Richard Burgin, he affirmed, "The story is the message." He emphasized that he could love literature without searching for messages and symbols in every book he read, acknowledging that his own life was interwoven with his stories in one way or another. He noted, "The only problem in the second half of the twentieth century is that there aren't enough stories, and without a story, words become meaningless."

Throughout his writing, Bashevis-Singer's persona as a believer emerged, even though he did not adhere to religious commandments in his childhood. A recurring theme in his works is the characters' contemplation of God's existence and questions about the nature of creation and human existence.

"Relations with God are relations of protest," he once said. "I am not capable of rising because to rise, you need some force. But to protest, you don't need any force."

In his writings, the devil often serves as a central figure, tempting Orthodox Jews in various ways to sin, to believe that "there is no justice, and there is no Judge," or to apostatize. These temptations lead to inner conflicts and madness in his characters.

Bashevis-Singer frequently blends Jewish beliefs, Kabbalistic concepts, and names of angels and demons, such as the bitter angel Ketev Meriri, into his narratives against the backdrop of simple Jewish lives. Descriptions of daily religious practices, including prayers, tefillin, kosher dietary laws, and Shabbat observance, are integral elements of many of his stories.

Bashevis-Singer's extensive knowledge, rooted in classical literature he read during his childhood hidden "under the table," such as the works of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, as well as books on philosophy, is evident in his thought-provoking narratives. He drew inspiration from Schopenhauer, Baruch Spinoza, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Nietzsche, which is noticeable in his literary works.

In his writing, a central theme is the ideological struggle between faith and religion on one hand, and rationality on the other. His approach to Judaism is that of a modern man, but with a tinge of nostalgia for the old Jewish ways as prescribed by the Torah. He often describes himself as a Jew by choice rather than by fate, and the answer to the question, "Who is a Jew?" relates to an individual's desire to belong to a particular nationality.

Bashevis-Singer's writing also delves into explicit and passionate descriptions of sexual desires. An illustrative example is the story "The Witch" from his collection "Desire." In his conversation with Burgin, he explained, "The best contact with humanity is through sex. Here, you learn many things about life, more than in any other way, because in sexual relationships and love, the human character is exposed, more than in any other way."

Bashevis-Singer had the ability to combine the most mundane aspects of daily life with the dramatic and fateful, sometimes concluding his stories with characters finding solace or suffering from the fate imposed upon them (as seen in "The Short Friday" and "Yarmolinsky and Keilah"), or succumbing to their sins and yielding to their evil inclinations (as in "Zeydele the Papercutter"). However, some stories also depict characters finding redemption and inheritance (as in "The Little Shoemakers").

Many of Bashevis-Singer's works were illustrated by renowned artists, including Raphael Soyer, Morris Sandek, Eric Carle, and Ruth Zarfati. His literary legacy remains a captivating journey through time, blending religion, philosophy, and human desires into thought-provoking narratives that continue to resonate with readers worldwide.

- יצחק בשביס-זינגרhe.wikipedia.org