מורשת גדולי האומה

בזכותם קיים

beta

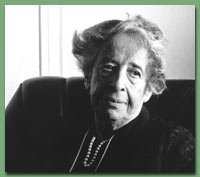

Hannah Arendt: A Life of Thought and Resilience

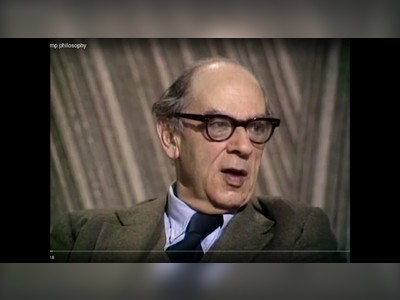

Hannah Arendt (born Johanna Arendt; October 14, 1906, Linden-Limmer, German Empire – December 4, 1975, New York) was a prominent Jewish-born public intellectual and philosopher from Germany. Her writings significantly contributed to the development of political philosophy, although she resisted being labeled a philosopher herself and preferred to align her work with the fields of political theory and the history of ideas. Arendt introduced the concept of "the banality of evil" in the context of Nazism and famously examined Adolf Eichmann's trial in Israel.

In the wake of the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany and a brief period of detention in 1933, Hannah Arendt emigrated from Germany to France and subsequently to the United States. After losing her German citizenship in 1937, she remained stateless until she acquired American citizenship in 1951, where she worked as a journalist and a lecturer at various institutions.

Arendt's philosophical thought revolves around the concept of political pluralism. According to this idea, there exists the potential for freedom and equality among human beings, and it is essential to adopt the perspective of others. In her view, political organizations should involve individuals who are capable and willing to participate more concretely. Due to this perspective, Arendt was critical of representative democracy and favored forms of governance such as councils or direct democracy. In her writings on education, she challenged the notion of free education and ideas about children's rights, arguing for a return of authority to the educational establishment and the placement of the child within a hierarchical structure through discipline and authority.

Despite distancing herself from the label of "philosopher," Arendt's writings exhibit intellectual clashes with numerous philosophers throughout history, including Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, and political philosophers like Machiavelli and Montesquieu, as well as her contemporaries Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers. Thanks to her independent thinking, her theories on totalitarianism, and her existentialist philosophy, her name stands out in the discourse of our times. Arendt grounded her writings in philosophical, political, and historical documents, as well as biographies and literary works. Her interpretive approach to texts, influenced in part by Heidegger, helped establish her as an independent thinker across various academic domains.

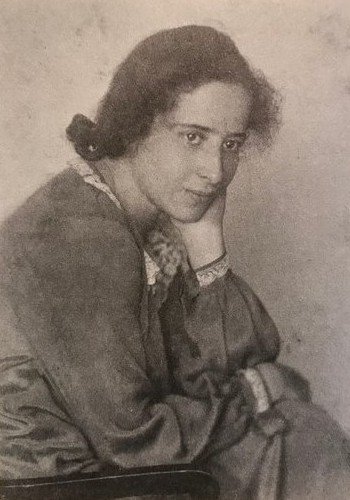

Hannah Arendt was born as Johanna Arendt in 1906 to Martha and Paul Arendt, Jewish middle-class individuals from Linden near Hannover, in northwestern Germany. Her family had its roots in Königsberg. Her grandfather, Max Arendt, served as the head of the city council in the early 20th century. Due to her father's illness and her mother's return to Königsberg, she was raised there before her third birthday. Her father passed away in 1913. During World War I, Martha and Hannah Arendt resided in Berlin. In 1920, her mother remarried Martin Beerwald, and the family settled in Königsberg. Her mother, who held social-democratic beliefs, instilled in her a liberal spirit and documented in her diary the intellectual and physical development of her daughter. Within the intellectual circles of Königsberg, it was taken for granted that girls should have the right to education. Through her grandparents and her mother, Arendt became acquainted with Reform Judaism. Although she did not officially belong to any religious community, she always considered herself a Jew.

At the age of 15, Arendt read "The Psychology of Worldviews" by Jaspers, and at 16, she delved into Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason" and "Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason." Additionally, she read poetry, especially Goethe, and novels in both German and French. The rigid school system led to a conflict with one of her teachers, which resulted in her leaving school and moving to Berlin, where she attended lectures on Christian theology, even though she did not possess a high school diploma. In Berlin, she immersed herself for the first time in the writings of Søren Kierkegaard. After her stay in Königsberg, she passed her high school exams as an external student.

In 1924, Arendt began her studies at the University of Marburg, where she studied philosophy with Martin Heidegger and Nicolai Hartmann, as well as Christian theology with Rudolf Bultmann. In addition to her studies, she learned ancient Greek.

A romantic relationship developed between Arendt, then 17 years old, and Heidegger, who was 35, married, and a father of two. In early 1926, Arendt decided to change her place of study and spent one semester with Edmund Husserl at the University of Freiburg. Later, she studied philosophy at the University of Heidelberg, where she received her doctorate in 1928 under the supervision of Karl Jaspers for her thesis on "The Concept of Love in the Thought of Augustin." Arendt maintained close friendships with Jaspers until his death.

In Marburg, Arendt maintained a low profile to conceal the nature of her relationship with Heidegger. She cultivated social relationships primarily from her time in Königsberg. In Heidelberg, Arendt expanded her circle of friends, which included the Jewish Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann, philosopher Karl Frankenstein, and Jewish historian Erwin Levinsohn. The lectures of poet Friedrich Gundolf brought her into contact with other intellectual figures in Heidelberg. A significant influence on Arendt was Kurt Blumenfeld, a prominent figure in German Zionism, who investigated the "Jewish Question" and the phenomenon of assimilation. In a letter from 1951, she acknowledged that it was thanks to Blumenfeld that she gained an understanding of the situation of the Jews.

In her journey through life, Hannah Arendt's intellectual curiosity and courage in the face of adversity continue to inspire scholars and thinkers worldwide.

Arendt's philosophical thought revolves around the concept of political pluralism. According to this idea, there exists the potential for freedom and equality among human beings, and it is essential to adopt the perspective of others. In her view, political organizations should involve individuals who are capable and willing to participate more concretely. Due to this perspective, Arendt was critical of representative democracy and favored forms of governance such as councils or direct democracy. In her writings on education, she challenged the notion of free education and ideas about children's rights, arguing for a return of authority to the educational establishment and the placement of the child within a hierarchical structure through discipline and authority.

Despite distancing herself from the label of "philosopher," Arendt's writings exhibit intellectual clashes with numerous philosophers throughout history, including Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, and political philosophers like Machiavelli and Montesquieu, as well as her contemporaries Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers. Thanks to her independent thinking, her theories on totalitarianism, and her existentialist philosophy, her name stands out in the discourse of our times. Arendt grounded her writings in philosophical, political, and historical documents, as well as biographies and literary works. Her interpretive approach to texts, influenced in part by Heidegger, helped establish her as an independent thinker across various academic domains.

Hannah Arendt was born as Johanna Arendt in 1906 to Martha and Paul Arendt, Jewish middle-class individuals from Linden near Hannover, in northwestern Germany. Her family had its roots in Königsberg. Her grandfather, Max Arendt, served as the head of the city council in the early 20th century. Due to her father's illness and her mother's return to Königsberg, she was raised there before her third birthday. Her father passed away in 1913. During World War I, Martha and Hannah Arendt resided in Berlin. In 1920, her mother remarried Martin Beerwald, and the family settled in Königsberg. Her mother, who held social-democratic beliefs, instilled in her a liberal spirit and documented in her diary the intellectual and physical development of her daughter. Within the intellectual circles of Königsberg, it was taken for granted that girls should have the right to education. Through her grandparents and her mother, Arendt became acquainted with Reform Judaism. Although she did not officially belong to any religious community, she always considered herself a Jew.

At the age of 15, Arendt read "The Psychology of Worldviews" by Jaspers, and at 16, she delved into Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason" and "Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason." Additionally, she read poetry, especially Goethe, and novels in both German and French. The rigid school system led to a conflict with one of her teachers, which resulted in her leaving school and moving to Berlin, where she attended lectures on Christian theology, even though she did not possess a high school diploma. In Berlin, she immersed herself for the first time in the writings of Søren Kierkegaard. After her stay in Königsberg, she passed her high school exams as an external student.

In 1924, Arendt began her studies at the University of Marburg, where she studied philosophy with Martin Heidegger and Nicolai Hartmann, as well as Christian theology with Rudolf Bultmann. In addition to her studies, she learned ancient Greek.

A romantic relationship developed between Arendt, then 17 years old, and Heidegger, who was 35, married, and a father of two. In early 1926, Arendt decided to change her place of study and spent one semester with Edmund Husserl at the University of Freiburg. Later, she studied philosophy at the University of Heidelberg, where she received her doctorate in 1928 under the supervision of Karl Jaspers for her thesis on "The Concept of Love in the Thought of Augustin." Arendt maintained close friendships with Jaspers until his death.

In Marburg, Arendt maintained a low profile to conceal the nature of her relationship with Heidegger. She cultivated social relationships primarily from her time in Königsberg. In Heidelberg, Arendt expanded her circle of friends, which included the Jewish Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann, philosopher Karl Frankenstein, and Jewish historian Erwin Levinsohn. The lectures of poet Friedrich Gundolf brought her into contact with other intellectual figures in Heidelberg. A significant influence on Arendt was Kurt Blumenfeld, a prominent figure in German Zionism, who investigated the "Jewish Question" and the phenomenon of assimilation. In a letter from 1951, she acknowledged that it was thanks to Blumenfeld that she gained an understanding of the situation of the Jews.

In her journey through life, Hannah Arendt's intellectual curiosity and courage in the face of adversity continue to inspire scholars and thinkers worldwide.

- חנה ארנדט – ויקיפדיהhe.wikipedia.org