מורשת גדולי האומה

בזכותם קיים

beta

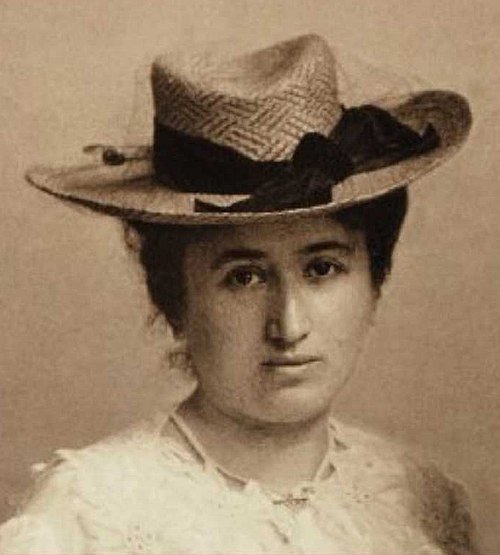

Rosa Luxemburg: The Revolutionary Thinker

Rosa (also Rosalia) Luxemburg (in Polish: Róża Luksemburg, in German: Rosa Luxemburg) was a Jewish Polish-German revolutionary and Marxist feminist theoretician. She met a tragic end, being assassinated by members of the Freikorps after the failure of the Spartacist Uprising, a communist uprising she had led.

Childhood and Adolescence

Rosa Luxemburg was born in the town of Zamość in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire, to a Jewish family of modest means. Her mother, Lina, came from a religious background and was well-read in religious texts. Her father, Eliasz (later Edward), worked as a timber merchant. She was the youngest of five children in her family. In their household, both German and Polish were spoken, and Rosa learned Russian as well. The Luxemburg family was known for their love of literature, and they often engaged in discussions about the world and its affairs.

The family eventually moved to Warsaw, and when Rosa was five years old, she developed a hip ailment that confined her to bed for a year and left her with a lifelong limp. Between 1880 and 1887, she attended a gymnasium in Warsaw, excelling in her studies. She learned four languages - Yiddish, Polish, German, and Russian - and developed a passion for both spoken and written language. At a young age, she began to engage in political activities within the Polish socialist movement. When she was around 17 years old, she had to flee to Switzerland to avoid arrest for her political activities. In Switzerland, she continued her education at the University of Zurich, studying natural sciences, law, and economics, eventually earning a doctorate in political science in 1897 with a thesis on "The Industrial Development of Poland."

In Zurich, Rosa met the revolutionary Leo Jogiches (also known as Leopold Jogiches), with whom she developed a personal and intellectual relationship that would profoundly influence her life. Together, they opposed the nationalism of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) and founded the newspaper "Workers' Cause" in 1893. In the newspaper, Luxemburg expressed her views on the need for a revolution in Poland and argued that it could only succeed if it was part of a broader revolution in neighboring countries like Germany, Austria, and Russia. She believed that the struggle against capitalism was more important than Polish national independence. Unlike Lenin, who supported the right of nations to self-determination, Luxemburg did not recognize the right to self-determination for nations.

In 1897, Rosa Luxemburg moved to Germany, where she married Gustav Lübeck, a German socialist, in order to acquire German citizenship and become active within the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). However, their marriage was largely a formality, and they did not lead a family life together.

From 1907 to 1914, Luxemburg served as a lecturer at the SPD's party school in Berlin.

Revolutionary Thinker

In 1903, Luxemburg played a prominent role in the debate between Eduard Bernstein and August Bebel over the issue of "revisionism." At the heart of the debate was the electoral success of the German Social Democratic Party, which garnered around three million votes and eighty-one seats in the Reichstag. Bernstein and his revisionist supporters saw this as an opportunity to participate in government and obtain ministerial positions, such as deputy presidency of the Reichstag. Luxemburg, along with Karl Liebknecht, opposed this idea and saw it as collaboration with the bourgeoisie they sought to overthrow. Luxemburg believed in revolution, not peaceful integration into the existing system. She argued that the proletariat needed to overthrow capitalism, not merely seek reforms within it. Unlike Lenin, who saw the right of nations to self-determination, Luxemburg did not believe in national independence but rather in international revolution.

Luxemburg was a vocal critic of World War I and predicted the collapse of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With the outbreak of the war, she, together with Liebknecht, founded the Spartacus League, initially as part of the SPD and later as a separate party. This organization served as the foundation for the German Communist Party. During this time, Luxemburg was arrested and sentenced to two years in prison. While in prison, she continued to write and engage in political activities, expressing her support for Lenin and the Bolshevik Revolution. However, she also criticized some aspects of their approach.

Luxemburg had complex views on violence within the context of a communist revolution that aimed to transfer power to the working class. In some of her writings, she opposed violence, such as in her 1911 article "The Utopia of Peace." However, in other instances, she refused to condemn the use of force, as seen in her article "What Does the Spartacus League Want?" where she called for resistance against what she perceived as violence from the bourgeoisie. She believed that in the current class struggle, the message to the enemy should be: "We will respond to the brutality with brutality!" Luxemburg criticized the reformism of the German Social Democrats even more vehemently than she criticized Lenin, believing in revolution through non-violent means like strikes and civil disobedience but not ruling out violent resistance when confronted by state violence.

In November 1918, Luxemburg was released from prison as part of a general amnesty granted by the Chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, during the waning days of the Kaiser's rule and before the proclamation of the Weimar Republic. During this period, the Spartacists made attempts to bring about a communist revolution in Germany, following the model of the Russian Revolution - a country defeated in the war, the collapse of the monarchy, and the establishment of workers' councils as centers of power. The young republic resisted these attempts, leading to massive demonstrations by workers and released soldiers. While Luxemburg considered these actions premature and adventurous, she stood alongside the leaders of the workers, delivering speeches daily. Her final speech was given at the founding congress of the German Communist Party.

On January 15, 1919, Rosa Luxemburg, along with Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck, was arrested by members of the Freikorps, a right-wing paramilitary group composed of demobilized soldiers. For several days, their fate remained unknown. Out of love for Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches, who had tried to alert authorities to her disappearance, was also arrested and subsequently murdered. Four months later, Luxemburg's body was found in a canal in the heart of Berlin's Tiergarten Park, where a modest monument now stands in her memory. It appeared that she had been brutally beaten, possibly shot, and her body had been thrown into the water. She was buried in the central Friedrichsfelde Cemetery in Berlin.

Her Legacy

In East Germany, created after World War II, Luxemburg was considered a national hero, and a square in Berlin was named after her. After German reunification, the city of Berlin decided to keep her name on the square.

Rosa Luxemburg's writings and ideas continue to influence leftist political thought and activism to this day. Her work on imperialism, capitalism, and the revolutionary potential of the working class remains relevant in discussions about social justice and systemic change. Her legacy lives on as an embodiment of the enduring struggle for a more just and equitable world.

- רוזה לוקסמבורגhe.wikipedia.org