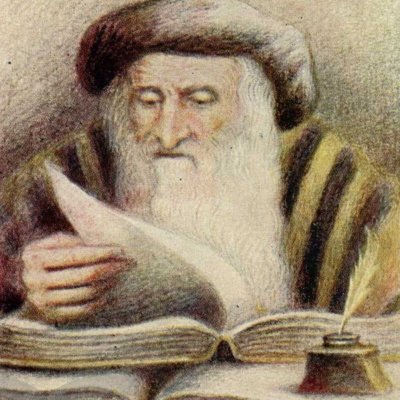

Rabbi Saadia Gaon: A Scholar of Babylonian Jewry

Rabbi Saadia Gaon's influence on Jewish scholarship, particularly in Babylon, was profound. His comprehensive knowledge of diverse subjects, dedication to preserving the Jewish calendar, and his groundbreaking works in both Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic, made him a luminary figure in Jewish history. Though he faced challenges and controversies, his legacy endures as a scholar who made invaluable contributions to the development of Judaism during the medieval period.

Rabbi Saadia ben Joseph Al-Fayyumi Gaon (July 882 CE – May 21, 942 CE), often abbreviated as RSG, was a prominent figure in Jewish scholarship hailing from Babylon. At the age of 46, he was appointed as the head of the Sura Yeshiva in Baghdad.

His literary output was vast, covering a wide array of subjects, including the Hebrew language and its grammar, poetry, biblical commentary, as well as theological and philosophical themes. In many respects, he is considered a pioneering figure, particularly as the first to systematically study and analyze the Hebrew language under the influence of the meticulous Arabic grammarians of his time.

This makes him one of the early Jewish grammarians of the Middle Ages. His written language was Judeo-Arabic, and he is among the earliest rabbis to extensively write in this language, establishing the foundation of Judeo-Arabic literature. He was also the first to compile a comprehensive philosophical work in Jewish philosophy, known as "Emunot ve-De'ot" (Beliefs and Opinions). Additionally, he engaged with the Karaites in literary and theological debates.

Early Life

Rabbi Saadia was born to Joseph Al-Fayyumi in the village of Dilaz in the Faiyum district of Upper Egypt, hence his epithet "Al-Fayyumi." In his youth, he left Faiyum and wandered through various regions, including the Land of Israel, Syria, and Babylon. Some suggest that he may have also traveled to Yemen.

According to later accounts, Rabbi Saadia was believed to be a descendant of the Tanna Rabbi Hanina ben Dosa, and there is some contention about whether he held a clerical position. However, he faced opposition from certain community members who disputed his legitimacy.

Education

Later accounts suggest that Rabbi Saadia studied under Abu Kathir Yaḥya ibn Zakariyya al-Ṣūfī al-Ṣayrafī, a noted Jewish scribe from Tiberias, who followed the Karaite tradition. During his youth, Rabbi Saadia acquired a wealth of knowledge in Hebrew linguistics, grammar, the Bible, Mishnah, Talmud, and Jewish law. He also delved into "the sciences and the wisdom of the nations," referring to general science and philosophy. In those years, the Arab culture in Egypt and its surroundings was flourishing, and Greek science had previously left its mark. These influences shaped his intellectual development, and he later developed a connection with the philosopher Isaac ben Solomon Israeli.

Migration to Babylon

At an unknown point, Rabbi Saadia migrated to Syria and, before 921 CE, established his residence in Baghdad, Iraq. Shortly before his arrival in Baghdad, he played a role in a dispute over the determination of the Jewish calendar, during which he became acquainted with the leaders of the Jewish community, including its rabbis and wealthy members.

These community leaders recognized his scholarly abilities and appointed him as the "Aluf" (leader) of the Pumbedita Yeshiva. In 928 CE, he was appointed to lead the renewed Sura Yeshiva, which was also located in Baghdad alongside the Pumbedita Yeshiva. This appointment was somewhat unconventional, as it was not common to appoint someone from outside the local community, especially someone not from prestigious families in the city.

Rabbi Saadia's unyielding character led to a conflict with the head of the Jewish exile (Gaon) in Babylon, resulting in a bitter estrangement between them and his removal from the leadership of the Sura Yeshiva. The rift persisted for several years, but eventually, prominent figures succeeded in reconciling the two parties, allowing Rabbi Saadia to return to his position as the head of the Sura Yeshiva. He held this position until his passing in 942 CE, when he was almost sixty years old.

His Death and Legacy

Accounts of his passing state: "The years of the life of our master, may his memory be blessed, were slightly less than sixty years; he ruled for fourteen of them in Mahuzah [a reference to the city of Pumbedita], lacking four days. He passed away on Monday night, at the end of the middle watch, on the twenty-sixth day of the month of Iyyar in the year one thousand two hundred and fifty-three (corresponding to 942 CE). His death occurred less than a year after he was removed from office."

Later traditions from the 18th century mention his grave in Safed, but there is no definitive evidence to confirm these accounts.

His Family

Rabbi Saadia had two sons, both of whom achieved significant scholarly success in the Babylonian yeshivas. She'arit, who studied at the Sura Yeshiva during his father's leadership, earned the title of Aluf. His other son, Dosa, was likely named after Rabbi Hanina ben Dosa, one of Rabbi Saadia's claimed ancestors. Dosa served as the head of the Sura Yeshiva between 1013 and 1017, following the passing of Rabbi Hefni Gaon.

The Calendar Controversy

One of the most significant controversies Rabbi Saadia was involved in centered around the determination of the Jewish calendar years 921-923 CE. The dispute revolved around the calculation of the "Molad Zaken" (the mean lunar conjunction) in fixing the dates of Rosh Chodesh (the beginning of the Jewish month). According to Ben Meir's calculation, in 921 CE, there was a missing year in the calendar, while the Babylonian scholars maintained that it was a complete year.

Ben Meir instructed his disciples to celebrate the holidays according to his calculations, but the Babylonian scholars, including David ben Zakkai and Rabbi Saadia Gaon, strongly disagreed and contended that Ben Meir had made an error. As a result, Passover was celebrated on different days in the Land of Israel and Babylonia, leading to significant confusion among Jewish communities.

The disagreement led to a flurry of letters and correspondences between the two camps. Ben Meir held firm in his position, insisting that only the scholars of the Land of Israel had the authority to determine the calendar, emphasizing their higher authority compared to the Babylonian scholars. This dispute eventually led to the adoption of Rabbi Saadia Gaon's calendar calculation in the Land of Israel, as documented by Maimonides in his time.

- רב סעדיה גאון – ויקיפדיהhe.wikipedia.org