Max Nordau: A Zionist Visionary and Intellectual

Max Nordau was a complex figure who made significant contributions as an intellectual, Zionist leader, and advocate of "Muscular Judaism." His critique of contemporary European culture, along with his role in shaping the Zionist movement, left a lasting impact on Jewish history and the discourse of his time.

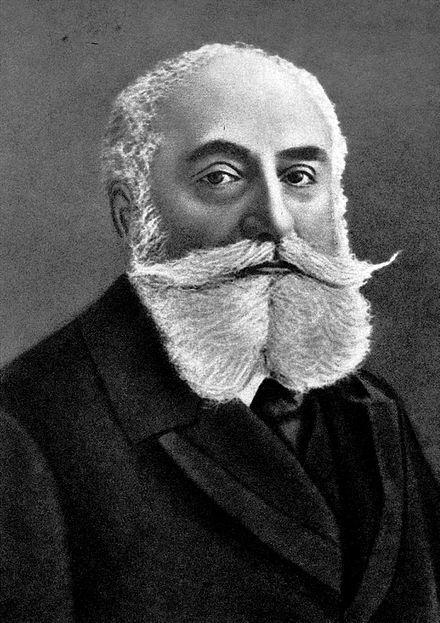

Max Nordau, at times referred to as "Nordoi" in Yiddish, was born on July 29, 1849, in Pest, Hungary (now Budapest), and passed away on January 23, 1923, in Paris. He was a prolific thinker, orator, author, physician, and a Hungarian-born Jew, known as one of the founders of the Zionist movement and a proponent of the "Muscular Judaism" ideology.

Family and Early Years

Max Nordau was born with the name Simon (Shmuel) Maximilian (Meir) Südfeld to an Orthodox Jewish family with Portuguese Jewish ancestry in Pest, Hungary. His father, Gabriel Südfeld, was a Hebrew poet and scholar.

Gabriel Südfeld, born in 1799 in Krakow, then part of the Grand Duchy of Poznań, was ordained as a rabbi by prominent rabbis such as Jacob Lorberbaum and Akiva Eger. He worked as a tutor in the households of rabbis Solomon Judah Rapoport, Moses Sofer, and the Fischhof family, where he taught Adolf Fischhof for six years. Gabriel Südfeld passed away in 1872.

Nordau recalled that his father taught him Hebrew as a child. His mother, from the Nelken family in Miskolc, passed away on January 2, 1900, and was buried in Paris. According to Nordau, his parents called him "Shmuel" at home, reserving the name "Max" for use in the presence of strangers.

Nordau began his education in a Jewish school but transitioned to a state-run Catholic gymnasium at the age of 15, and later attended a Calvinist gymnasium where he completed his graduation exams. Eventually, he earned a medical degree from the University of Pest. After his studies, he worked as a writer for several small newspapers in Budapest, including the Pestel Lloyd. In the spring of 1873, he moved to Berlin and began writing under the pseudonym Max Nordau, meaning "Northern Brother" in contrast to his original name, Südfeld, meaning "Southern Field." On April 11, 1874, he officially adopted the name "Nordau."

In 1880, Nordau moved to Paris, where he worked as a writer for the Berlin-based liberal newspaper Vossische Zeitung and also wrote for the Viennese newspaper "Die Neue Freie Presse." Nordau lived in Paris until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, which, as a Hungarian citizen, forced him to leave France. He then relocated to Madrid, Spain, where he resided for six years before moving to London in 1920.

Nordau, who married a Protestant woman, identified himself as a "cultivated Jew" who had distanced himself from traditional Jewish practices and Torah study by the age of fifteen. He considered himself more aligned with German culture, stating, "By the time I reached fifteen, I had abandoned the Jewish way of life and the study of the Torah... Judaism remained for me nothing more than a memory, and since then, I always felt purely German."

Intellectual Contributions

Throughout his life, Nordau established himself as a prominent intellectual, particularly in the realms of society, religion, and art. His articles often sharply criticized the superficiality and direction of European culture in his time, inciting numerous controversies and storms. He was one of the leading figures of the conservative and preservationist strain of 19th-century positivism, authoring several controversial books, including "The Conventional Lies of Our Civilization" (Die conventionellen Lügen der Kulturmenschheit), published in 1883 and translated into 15 languages, including Chinese and Japanese, "Degeneration" (Entartung, 1892), and "Paradoxes" (1896).

His most famous and discussed work is "Degeneration," in which Nordau harshly criticized various aspects of modern culture as "decadent," portraying leading artists of his time as mentally unstable or intellectually feeble and highlighting the connection between their artistic work and their physical weaknesses. In the concluding chapter of the book, Nordau called for society to combat harmful influences to heal what he perceived as a pandemic of moral decay.

Nordau's work stirred significant controversy upon its publication, with one of the most notable critiques coming from the renowned Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, who accused Nordau of publishing a pathological book authored by a mentally ill individual.

Zionism

In 1892, Nordau became acquainted with Theodor Herzl and the ideas of Zionism. Unlike Herzl, who emphasized the creation of a Jewish state with liberal European characteristics, Nordau sought to revive Jewish national honor through romantic means rooted in historical consciousness. Nevertheless, Nordau recognized Herzl as a true partner in his sharp critique of the "Protocols of the Elders of Zion," a document he blamed for economic crises, social turmoil, and political manipulation caused by the speculative financial powers.

Nordau played a substantial role in the Zionist Congresses, serving as vice-president from the First to the Sixth Congress and as president from the Seventh to the Tenth Congress. Later, he withdrew from active participation in the Zionist Congresses due to disagreements with practical Zionists. Nordau was a leading figure in the political Zionist movement and was instrumental in founding the youth movement "Young Maccabi."

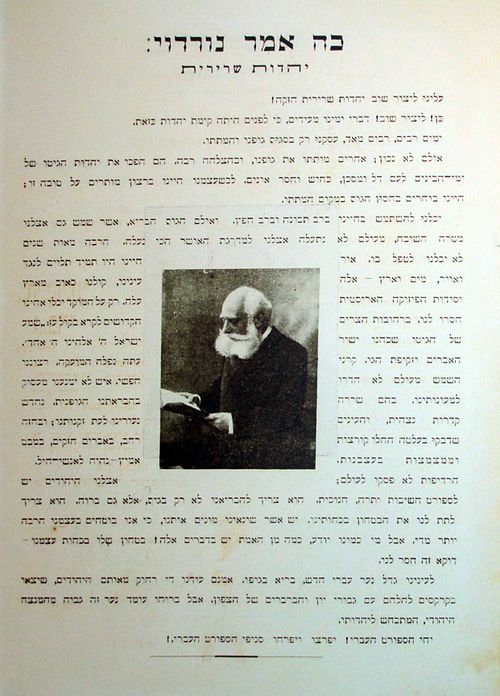

During the Second Zionist Congress in 1898, Nordau called for the restoration of the "lost might of the Jewish people" and advocated returning the image of "the fighting Jew" to the Jewish diaspora. This idea was influenced by the organic theories popular at the time. According to Nordau, physical rejuvenation of Judaism should precede its moral and political revival: "We must create a strong Jewish people again! Yes, create it again! Our ancient history testifies that such a Judaism existed... We chose physical inoculation over physical death." The concept of "Muscular Judaism" inspired the formation of Jewish sports organizations worldwide, with names representing strength and power, such as "Maccabi," "Samson," "HaKoach," and "Bar Kochba Berlin," among others.

- מקס נורדאוhe.wikipedia.org