Jehuda Abravanel: Renaissance Jewish Philosopher and Poet

Jehuda Abravanel stands as a unique figure at the crossroads of cultures and philosophies. He was the last Jewish philosopher whose thought drew from Jewish sources while also embracing the intellectual traditions of his time. He managed to capture the development of early Italian philosophy, yet he freed himself from the constraints of philosophy that aimed solely to explain ancient authors.

In the words of Karl Gebhardt, a researcher of Abravanel and the editor of his works in German, "Jehuda Abravanel stands between cultures. He is the last Jewish philosopher who thinks not as a Jew for Jews, as the Jewish philosophers in Spain did, but as a philosopher for a circle of educated philosophers who stand above any specific religion."

Jehuda Abravanel's life and works continue to inspire scholars and readers alike, serving as a testament to the intellectual richness of the Renaissance period and the enduring impact of Jewish philosophers on Western thought.

Jehuda Abravanel, also known as Leone Ebreo, was a prominent figure in the 15th and 16th centuries, making significant contributions as a rabbi, physician, philosopher, and poet. Born around 1460 in Portugal, he lived through a time of great upheaval and cultural transformation. His life journey took him from Portugal to Spain and eventually to Italy, where he left a lasting legacy through his writings and philosophical outlook. This documentary-style article delves into the life and works of Jehuda Abravanel, shedding light on his impact during the Renaissance period.

Early Life and Education

Jehuda Abravanel was born to Rabbi Don Yitzhak Abravanel in Portugal. In his youth, he pursued a medical education and gained recognition for his medical skills. However, his life took a dramatic turn in 1483 when he and his father fled to Castile, Spain, due to the persecution initiated by King João II against Don Yitzhak Abravanel. They settled in the city of Toledo.

In 1491, while still in Castile, Jehuda Abravanel became a father to a son named Yitzhak, named after his grandfather. Notably, this period marked a turbulent time for Jews in Spain, culminating in the expulsion of the Jewish population.

Exile to Italy

In the wake of the expulsion of Jews from Spain, both Don Yitzhak and Jehuda were forced to leave their newfound home and make their way to Italy, eventually reaching Naples. King Ferdinand of Spain, in a bid to prevent Jehuda from leaving, had plans to convert his younger son, Yitzhak, to Christianity. The intention was to keep the Abravanel family in Spain, but Jehuda and his son managed to escape to Italy.

Upon the French occupation of Naples in 1495, Jehuda moved to Genoa, where he practiced medicine while simultaneously working on his famous work "Dialoghi di Amore" ("Dialogues of Love"). It was during his time in Genoa that he received news of his eldest son, Yitzhak, converting to Christianity. Jehuda had another son, Samuel, who tragically passed away at the tender age of five.

Return to Naples and Later Years

In 1501, Jehuda Abravanel was called back to Naples to serve as a court physician. In 1503, he penned his renowned work "HaTehorah Al HaZman" ("The Exhortation on Time"), believed to have been written with the intent of persuading his son Yitzhak to return to Judaism.

However, in 1507, Jehuda left Naples under unclear circumstances, and there is limited information about these years in his life. Some speculate that he may have traveled to meet his son Yitzhak, who had returned to Judaism and left Portugal. There is a document from 1521 indicating Jehuda's efforts on behalf of the Jewish community in Naples.

The exact year of Jehuda Abravanel's death remains unknown, but by 1535, when his book "Dialoghi di Amore" was printed, he had already passed away.

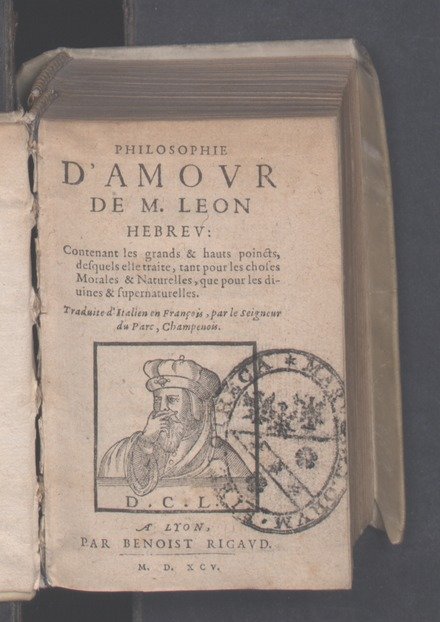

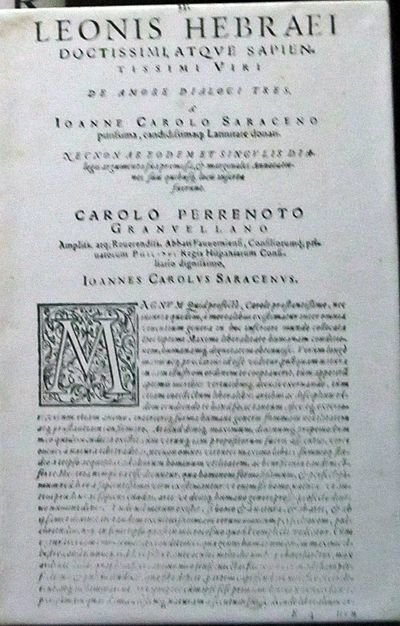

Legacy and "Dialoghi di Amore"

Jehuda Abravanel's most enduring contribution is his work "Dialoghi di Amore," written around 1502 but first printed in 1535 in Rome. The book gained immense popularity during its time and went through numerous Italian editions until 1607.

Remarkably, the book was translated twice into French, thrice into Spanish, once into Latin, and thrice into Hebrew. Although it was originally written in Italian, some researchers argue that it may have been composed in Spanish.

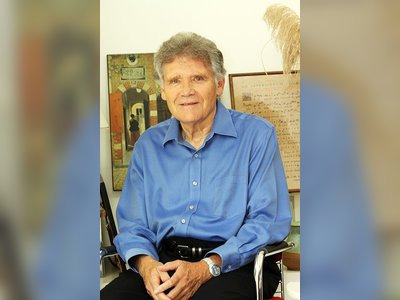

Despite the existence of a Hebrew translation of the book in the late 17th century, it wasn't printed in Hebrew until 1875, by the publishing house "Mekitzei Nirdamim," under the title "Vikuch Al HaAhavah" ("Discussion on Love"). A more recent translation was published in 1983 by Menachem Dorman, which included an introduction and annotations, under the Bialik Institute's auspices.

Jehuda Abravanel did not conceal his Jewish identity in "Dialoghi di Amore," even though the language of the book suggests it was written for a broader, non-Jewish audience. Some scholars argue that his Jewish identity granted him a certain freedom in his writing that might not have been attainable for a Christian philosopher of his time.

- יהודה אברבנאל – ויקיפדיהhe.wikipedia.org