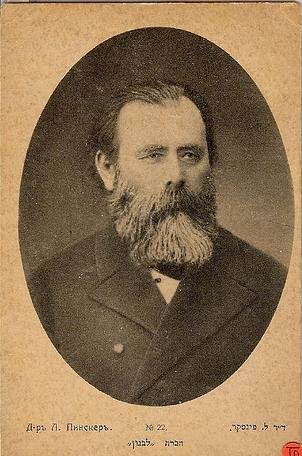

Yehuda Leib (Leon) Pinsker: The Pioneer of Jewish Nationalism

Yehuda Leib (Leon) Pinsker (in Yiddish: לעאָן פינסקער; in Russian: Лев (Леон) Семёнович or Йехуда Лейб Пинскер;) was born on the 1st of Tevet, 1821 (according to the Julian calendar, which corresponds to December 13; according to the Gregorian calendar, it is December 25) in Tomashov Lubelski, a town in Congress Poland under Russian rule. He was a physician, philosopher, and Jewish nationalist activist, considered one of the forefathers of Zionism and territorialism, known as the author of the book "Auto-Emancipation!"

Early Life and Education

Yehuda Leib Pinsker was born into a family that embraced the ideals of the Haskalah movement, an intellectual and cultural movement among Jews. During his childhood, his family moved to the Ukraine, settling in Odessa. His father, Menachem Mendel Pinsker, was a scholar well-versed in Talmud and the Bible.

Menachem Mendel Pinsker was among the early Jewish intellectuals who, disillusioned by the failure to secure equal rights for Jews in Russia, eventually turned towards Jewish nationalism. He had a deep connection to the Land of Israel, which was expressed through prayers for the rebuilding of the Temple and the coming of the Messiah.

His father's anguish over the plight of the Jewish people deeply influenced the young Pinsker and sparked his desire to improve the fate of the Jews. While Menachem Mendel Pinsker was dedicated to the welfare of his people, his traditional connection to the Land of Israel was a significant influence on his son's worldview, which would develop further in the future.

Initially, Pinsker believed that assimilation was the solution, but following the pogroms in the South of Russia, his views evolved, which he articulated in his book "Auto-Emancipation!"

Pinsker grew up in Odessa, a cosmopolitan and open-minded city that suffered less from the restrictive policies imposed by the Russian Empire. The Jewish intellectuals in Odessa enjoyed more freedom compared to those living in more conservative areas, where religious conservatism imposed limitations from within the Jewish community.

The atmosphere of the city played a crucial role in shaping Pinsker's character and his future course of action. Like many of his peers, Pinsker came from a background rooted in rabbinic tradition. However, he was sent to receive a modern secular education. He attended the Russian gymnasium in Odessa, where he studied in Russian (and German).

The focus of his studies was not only on language but also on Russian culture and history. During his school years, Pinsker was already a fervent advocate for the promotion of education, as the Russian government had imposed severe restrictions on Jews who adhered to tradition while favoring the educated elite among them.

Upon completing his studies at the gymnasium with distinction, Pinsker continued his education at the Odessa University, where he studied law at the "Lyceum of Richelieu." However, when he finished his formal education at the age of twenty-one and was ready to enter the legal profession, his Jewish identity prevented him from practicing law.

Pinsker turned to teaching and became a Russian language teacher at the modern Hebrew school in Kishinev. During this period, education was not only seen as a profession but also as an ideal among enlightened Jews, and education was perceived as the primary solution to the problems facing the Jewish community.

While teaching at the Kishinev school, Pinsker witnessed the repressive measures taken by Tsar Nicholas I, who opposed any form of free thought. During his reign, twenty-two censorship authorities operated, imposing strict controls on literature and journalism in Russia. Nicholas I sent a letter to the prominent Russian writers, insisting that "the word should be removed from the official dictionary."

Against this backdrop, Pinsker supported the establishment of a network of modern Jewish schools in Jewish communities. He saw this as a positive influence of general education on Jews within the Pale of Settlement.

After one year of teaching at the school, unable to tolerate the oppressive atmosphere and cultural backwardness prevailing in Kishinev, Pinsker decided to pursue his studies in a more enlightened and intellectually stimulating environment. He moved to Moscow and began studying medicine.

At Moscow University, the intellectual hub of Russia at the time, Pinsker found a connection between himself and a group of Westernizing intellectuals who were deeply involved in science and Western liberalism. These influences greatly shaped his thinking.

The economic conditions in Russia seemed to justify the Westernizers' ideas, which aligned with concepts of freedom and progress, fitting well with the situation of Russian Jews. At that time, there was optimism that these Western ideas, associated with liberalism, would eventually prevail.

In 1848, Pinsker completed his studies. Around the same time, Western Europe was experiencing a wave of national revolutions known as the "Spring of Nations," marked by the triumph of liberal thought. In contrast, in Russia, the forces opposing the Haskalah movement gained strength. Tsar Nicholas I, who sought to uproot liberal thought, imposed numerous restrictions. During his reign, the government enforced strict censorship and suppressed the study of history and philosophy.

The use of terms related to liberalism in literature and journalism was prohibited. After completing his studies, Pinsker dedicated his time to practicing medicine, where he demonstrated his empathy for the suffering of others and a willingness to take risks for the sake of helping others.

The death of Nicholas I and the end of the Crimean War in 1856 marked the conclusion of the first chapter of Pinsker's life. During this period, he did not engage in public matters, but it was a fertile ground for his spiritual and intellectual growth, which would significantly influence Jewish Zionist thought in the future.

The Establishment of the Russian Jewish Bilu Movement

Pinsker's public activism began with the change of leadership in the Russian Empire, particularly with the ascension of Tsar Alexander II, who pursued a more liberal policy and cooperated with intellectuals while easing some of the censorship restrictions. This period saw improvements in various aspects of life in Russia, bringing it closer to Western European standards.

In 1860, against this backdrop, a group of Jewish intellectuals gathered in Odessa to establish a new Russian-language newspaper called "Razsvet" (Russian: "Dawn"), which focused on Jewish issues. The newspaper, however, closed after a year due to censorship restrictions that prevented it from addressing various topics.

Shortly afterward, Pinsker launched a new newspaper called "Tzion," in which he expressed his views and perspectives on the correct approach to the Jewish question. The goal of "Tzion" was to strengthen the national spirit among Jews who were trying to assimilate into Russian society. Pinsker wrote:

"History has imposed two obligations on the Jews: one is to be attentive to their current needs and their homeland, and the other is to remain true Jews. While they are busy fulfilling the first obligation, Jews have distanced themselves not only from their heritage and lineage but also from any sense of identity. Our mission, therefore, is to revive in their hearts the great history of the Jewish people and clarify their purpose in the present."

In his perspective, Pinsker downplayed the religious aspect of Jewish life in Russia and emphasized the national Jewish identity. His concept of Jewish nationalism sought to rally the Jewish people around a sense of belonging and shared history.

This emphasis on national identity led to the eventual formation of the Bilu movement, which aimed to promote Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel and laid the groundwork for future Zionist movements.

In 1882, a significant event occurred that would further shape Pinsker's nationalist vision. A series of pogroms swept through the South of Russia, particularly in the region of Elizavetgrad (now Kirovohrad, Ukraine). These violent outbreaks shocked Pinsker and other Jewish intellectuals. The Russian government was either unwilling or unable to protect the Jewish population, leading many to lose faith in the possibility of achieving equal rights and acceptance in Russia.

The term "Zionism" was first coined by Nathan Birnbaum in his journal "Self-Emancipation" (Selbstemanzipation) in 1890. However, Pinsker's ideas laid the groundwork for the emergence of Zionism as a distinct political movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Pinsker's Influence on Zionism

Although Pinsker did not live to see the full realization of the Zionist movement, his ideas and writings played a crucial role in shaping the future of Jewish nationalism and Zionism. His book "Auto-Emancipation!" (in German: "Selbstemanzipation!") was published in 1882, the same year as the first Aliyah (Jewish immigration to Palestine) and the establishment of the first modern Jewish agricultural settlements in the Land of Israel.

In "Auto-Emancipation!," Pinsker argued that Jews could only achieve true emancipation and freedom by taking control of their destiny and returning to their ancestral homeland. He wrote:

"Auto-Emancipation! implies that we are not dependent on the decrees of others, and that we, the Jews, have the power to put an end to our persecution by establishing a homeland of our own."

Pinsker believed that the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine would not only provide physical safety but also serve as a catalyst for Jewish cultural and spiritual reawakening. He emphasized the need for self-help and self-reliance, as he had seen how external forces could be unreliable and hostile.

While Pinsker's book did not gain widespread recognition during his lifetime, it became an influential work in the years that followed, inspiring other Jewish thinkers and leaders who would go on to play key roles in the Zionist movement. Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, acknowledged Pinsker's contributions and saw him as a precursor to his own ideas. Herzl wrote in his diary:

"Pinsker was right. A return to Palestine will be our political messianic mission."

Pinsker's vision of Jewish self-determination and the establishment of a Jewish homeland continued to gain traction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The First Zionist Congress, organized by Herzl in 1897, marked a significant milestone in the Zionist movement, and Pinsker's ideas were part of the intellectual foundation of the congress.

Death and Legacy

Yehuda Leib Pinsker passed away on December 29, 1891, in Odessa at the age of 70. Although he did not live to see the full realization of his vision, his ideas and writings left an enduring legacy that played a crucial role in the development of modern political Zionism.

Pinsker's contributions to the Zionist movement and Jewish nationalism continue to be recognized and celebrated today. His emphasis on Jewish national identity, self-help, and the return to the ancestral homeland set the stage for the eventual establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. His book "Auto-Emancipation!" remains an important historical document and a testament to his commitment to the well-being and self-determination of the Jewish people.

In recognition of his contributions, there are streets, schools, and institutions named after Yehuda Leib Pinsker in Israel and other parts of the world. His life and work continue to inspire those who are passionate about the Jewish people's history, identity, and connection to the Land of Israel.

- יהודה לייב פינסקרhe.wikipedia.org