מורשת גדולי האומה

בזכותם קיים

beta

"One of the People"

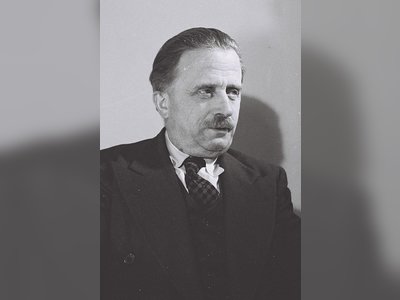

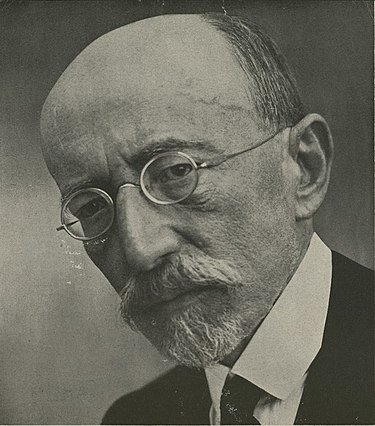

Asher Zvi Ginsberg, known by his literary pseudonym "Achad Ha'am," was a writer and philosopher who articulated the theory of the "spiritual center" in Zionism. Born in Ukraine, he immigrated to the Land of Israel and passed away in Tel Aviv five years later.

Achad Ha'am was the pen name of Asher Zvi (Hirsch) Ginsberg, born on August 18, 1856, in Skvyra, Kiev Province, Ukraine. He was a leading Zionist thinker, the founder of the spiritual Zionist movement, and a prominent figure in secular Jewish nationalism.

"What we lack above all, even before the 'national decision,' is a fixed place for a spiritual national center, which will be a 'safe haven' not for Jews, but for Judaism."

"If we choose life, we must build for ourselves a separate home in a faithful place – where is a faithful place other than the heritage of our fathers? We must then dedicate our material and moral strengths to our one salvation: the revival of our people in the land of our ancestors."

Achad Ha'am's vision aimed to adapt Jewish culture to the modern age and education, renewing it with the help of a cultural center in the Land of Israel. The Zionism he envisioned was called "spiritual Zionism."

Achad Ha'am believed that the driving force behind the Zionist movement was not physical hardship. According to his view, the emancipation and integration of Jews into the surrounding society led to the erosion of Jewish cultural-national identity. The modern era, marked by secularization and equal rights, caused the decline of religion since it could no longer sustain Jewish cultural uniqueness. He referred to this problem as the "crisis of Judaism." Achad Ha'am did not see the Zionist movement as a solution to the Jewish crisis for all Jews. Instead, he sought to address the "crisis of Judaism" by establishing a center for modern secular Hebrew culture.

Achad Ha'am proposed the establishment of a spiritual center in the Land of Israel. He did not believe that all Jews from the diaspora would immigrate to the Land of Israel. Instead, he thought that a Jewish cultural center in Israel could save Jewish culture from complete destruction and elevate the people above the cultural morass in which they were sinking. He believed that the sovereign state was merely a tool to encapsulate the spirit of the people.

Achad Ha'am did not believe that it was possible to establish a state where all Jews would settle, like any other country in the world. He did not believe that the majority of the ten million scattered Jews in Europe would come to settle in a distant land in the heart of the Middle East.

In his view, a spiritual center in Israel was essential, a focal point for national, spiritual, and cultural identity for the majority of Jews who lived in the diaspora. He envisioned this center as a place where people would engage in all aspects of Jewish culture: establishing universities, studying and researching in them, speaking Hebrew, creating literature in Hebrew, studying Jewish sources, striving to embody Jewish values, and creating a model of Jewish culture and modern thought. In the long term, the Land of Israel would become the nation's center, and perhaps in the distant future, this center would produce individuals capable of founding a state.

Early Life

Asher Zvi (Hirsch) Ginsberg was born in the summer of 1856 to a merchant father in the town of Skvyra, Kiev Province, Ukraine. He grew up in Odessa and received an education in medieval philosophy, with an emphasis on Maimonides' "Guide for the Perplexed." He also self-taught European languages, including Russian, German, French, English, and Latin.

After marrying Rebekah, the daughter of Mordecai Solomon Sonnabend (son of Joseph Isaac Sonnabend), in 1873, he continued his private studies, particularly in philosophy and science. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to gain admission to a university several times and remained an autodidact. Due to his strong rationalist tendencies, he first distanced himself from Hasidism and later completely turned away from religious belief. He became one of the prominent figures of the Hibbat Zion (Love of Zion) movement.

He settled in Odessa, where his father placed him in charge of a distillery belonging to the family.

In 1894, he attempted to publish an encyclopedia of all matters concerning Judaism titled "Otzar HaYahadut" (The Treasury of Judaism). He engaged in negotiations with various parties in this endeavor and tried to secure financial support from Zeev Jabotinsky, a tea merchant and philanthropist. However, he was unable to publish it in the end.

In 1907, Ginsberg moved to England, where he established and managed the London branch of the "Tea and Teaschke" company for Klonymus Zeev Wissotzky. He was also involved in the establishment of the Hebrew Technion in Haifa, alongside his son-in-law, Samuel Pinson, who married his daughter Leah Ginsberg. He also supported Chaim Weizmann in his efforts to obtain the Balfour Declaration.

In 1922, he immigrated to the Land of Israel and initially settled in Jerusalem before moving to Tel Aviv.

The municipality of Tel Aviv acquired his former residence, which had belonged to Zeev Mosinzon, renovated it, and named the street where the house is located after him, calling it "Achad Ha'am Street" during his lifetime.

Achad Ha'am passed away from pneumonia in the winter of 1927, at the age of 70, and was buried in the Trumpeldor Cemetery in Tel Aviv.

He was the father of Leah Dvora, the wife of Samuel Joseph Pinson; Rachel, a lawyer and Doctor of Laws, who married the Russian poet Mikhail Osorgin; and Shlomo Ginsberg (Ginzburg), a Zionist activist, journalist, and diplomat. His sister, Dr. Esther Shimanovitz, was the first Hebrew-speaking female physician in Haifa.

Philosophy and Zionist Activity

In 1889, he published his article "Not This Way!" which called for a revolutionary change in the approach of the Hibbat Zion movement. In his view and belief, the Land of Israel was not intended to solve the existential or economic question of the Jews; it was not meant to be a physical refuge from the hardships of the diaspora. Its purpose was to address the spiritual and cultural problem of the Jewish people. It was not enough for the Jewish state to be a national home and refuge for Jews – it needed to have spiritual content that justified its existence. It had to be a source of moral light to the nations, a universal "lampstand of morals." Thus, he formulated and founded the spiritual Zionist movement. He adopted the literary pseudonym "Achad Ha'am," which means an ordinary person, as he signed his name at the end of the article.

He didn't limit his efforts to writings; he took practical steps and organized the Bnei Moshe organization, recruiting friends and supporters.

Following the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903, he was one of the initiators and signatories of "The Voice of the Call," an appeal by Jewish writers calling for self-defense. He urged limiting the Jewish struggle against the Russian Tsar only to the struggle for Jewish civil rights in the diaspora and for the rebirth of Jewish culture in the Land of Israel.

He also addressed the issue of a Hebrew university. He was opposed to establishing an educational institution like a European university in the Land of Israel. He believed that a university that was completely Jewish, serving the Jewish nation, should be established. In 1907, in a letter he published in the "Hapoel Hatzair" newspaper, he even proposed a curriculum for a Jewish university. A year later, he donated his entire library, which was one of the largest Hebrew libraries in the world, to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, which was still in the process of being established.

He frequently wrote letters to "Hapoel Hatzair," "Hashiloach," and other periodicals. One of his well-known essays, "The Ethical State," was published in "Hashiloach" and presented his idea of the purpose of the Jewish state as being primarily ethical. In it, he states that he supported Herzl's political activities, even though he was against them in principle because they aimed at physical well-being. However, Herzl's mission was to create the Jewish state, while Achad Ha'am was concerned with the question of what the state would be like when it was established.

While living in London, he published a collection of his writings in "Al Parashat Derachim," which contained articles he had written between 1889 and 1898, and "Kapaiim," a collection of his poems.

Legacy

Achad Ha'am's ideas had a significant influence on the Zionist movement, particularly in shaping the concept of cultural and spiritual Zionism. He emphasized the importance of Jewish culture and education as a means of preserving Jewish identity and believed that the Land of Israel should be the center of this cultural renewal.

Although his views often clashed with those of other prominent Zionist leaders like Theodor Herzl, who focused more on political and territorial aspects of Zionism, Achad Ha'am's ideas continue to resonate with many who see the cultural and spiritual dimensions of Jewish identity as central to the Zionist project.

Achad Ha'am's legacy can be seen in the continued emphasis on Hebrew language and culture in Israel, as well as in the ongoing debate over the nature and purpose of the Jewish state. His writings and ideas remain an important part of the intellectual history of Zionism and continue to be studied and discussed by scholars and thinkers today.

"What we lack above all, even before the 'national decision,' is a fixed place for a spiritual national center, which will be a 'safe haven' not for Jews, but for Judaism."

"If we choose life, we must build for ourselves a separate home in a faithful place – where is a faithful place other than the heritage of our fathers? We must then dedicate our material and moral strengths to our one salvation: the revival of our people in the land of our ancestors."

Achad Ha'am's vision aimed to adapt Jewish culture to the modern age and education, renewing it with the help of a cultural center in the Land of Israel. The Zionism he envisioned was called "spiritual Zionism."

Achad Ha'am believed that the driving force behind the Zionist movement was not physical hardship. According to his view, the emancipation and integration of Jews into the surrounding society led to the erosion of Jewish cultural-national identity. The modern era, marked by secularization and equal rights, caused the decline of religion since it could no longer sustain Jewish cultural uniqueness. He referred to this problem as the "crisis of Judaism." Achad Ha'am did not see the Zionist movement as a solution to the Jewish crisis for all Jews. Instead, he sought to address the "crisis of Judaism" by establishing a center for modern secular Hebrew culture.

Achad Ha'am proposed the establishment of a spiritual center in the Land of Israel. He did not believe that all Jews from the diaspora would immigrate to the Land of Israel. Instead, he thought that a Jewish cultural center in Israel could save Jewish culture from complete destruction and elevate the people above the cultural morass in which they were sinking. He believed that the sovereign state was merely a tool to encapsulate the spirit of the people.

Achad Ha'am did not believe that it was possible to establish a state where all Jews would settle, like any other country in the world. He did not believe that the majority of the ten million scattered Jews in Europe would come to settle in a distant land in the heart of the Middle East.

In his view, a spiritual center in Israel was essential, a focal point for national, spiritual, and cultural identity for the majority of Jews who lived in the diaspora. He envisioned this center as a place where people would engage in all aspects of Jewish culture: establishing universities, studying and researching in them, speaking Hebrew, creating literature in Hebrew, studying Jewish sources, striving to embody Jewish values, and creating a model of Jewish culture and modern thought. In the long term, the Land of Israel would become the nation's center, and perhaps in the distant future, this center would produce individuals capable of founding a state.

Early Life

Asher Zvi (Hirsch) Ginsberg was born in the summer of 1856 to a merchant father in the town of Skvyra, Kiev Province, Ukraine. He grew up in Odessa and received an education in medieval philosophy, with an emphasis on Maimonides' "Guide for the Perplexed." He also self-taught European languages, including Russian, German, French, English, and Latin.

After marrying Rebekah, the daughter of Mordecai Solomon Sonnabend (son of Joseph Isaac Sonnabend), in 1873, he continued his private studies, particularly in philosophy and science. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to gain admission to a university several times and remained an autodidact. Due to his strong rationalist tendencies, he first distanced himself from Hasidism and later completely turned away from religious belief. He became one of the prominent figures of the Hibbat Zion (Love of Zion) movement.

He settled in Odessa, where his father placed him in charge of a distillery belonging to the family.

In 1894, he attempted to publish an encyclopedia of all matters concerning Judaism titled "Otzar HaYahadut" (The Treasury of Judaism). He engaged in negotiations with various parties in this endeavor and tried to secure financial support from Zeev Jabotinsky, a tea merchant and philanthropist. However, he was unable to publish it in the end.

In 1907, Ginsberg moved to England, where he established and managed the London branch of the "Tea and Teaschke" company for Klonymus Zeev Wissotzky. He was also involved in the establishment of the Hebrew Technion in Haifa, alongside his son-in-law, Samuel Pinson, who married his daughter Leah Ginsberg. He also supported Chaim Weizmann in his efforts to obtain the Balfour Declaration.

In 1922, he immigrated to the Land of Israel and initially settled in Jerusalem before moving to Tel Aviv.

The municipality of Tel Aviv acquired his former residence, which had belonged to Zeev Mosinzon, renovated it, and named the street where the house is located after him, calling it "Achad Ha'am Street" during his lifetime.

Achad Ha'am passed away from pneumonia in the winter of 1927, at the age of 70, and was buried in the Trumpeldor Cemetery in Tel Aviv.

He was the father of Leah Dvora, the wife of Samuel Joseph Pinson; Rachel, a lawyer and Doctor of Laws, who married the Russian poet Mikhail Osorgin; and Shlomo Ginsberg (Ginzburg), a Zionist activist, journalist, and diplomat. His sister, Dr. Esther Shimanovitz, was the first Hebrew-speaking female physician in Haifa.

Philosophy and Zionist Activity

In 1889, he published his article "Not This Way!" which called for a revolutionary change in the approach of the Hibbat Zion movement. In his view and belief, the Land of Israel was not intended to solve the existential or economic question of the Jews; it was not meant to be a physical refuge from the hardships of the diaspora. Its purpose was to address the spiritual and cultural problem of the Jewish people. It was not enough for the Jewish state to be a national home and refuge for Jews – it needed to have spiritual content that justified its existence. It had to be a source of moral light to the nations, a universal "lampstand of morals." Thus, he formulated and founded the spiritual Zionist movement. He adopted the literary pseudonym "Achad Ha'am," which means an ordinary person, as he signed his name at the end of the article.

He didn't limit his efforts to writings; he took practical steps and organized the Bnei Moshe organization, recruiting friends and supporters.

Following the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903, he was one of the initiators and signatories of "The Voice of the Call," an appeal by Jewish writers calling for self-defense. He urged limiting the Jewish struggle against the Russian Tsar only to the struggle for Jewish civil rights in the diaspora and for the rebirth of Jewish culture in the Land of Israel.

He also addressed the issue of a Hebrew university. He was opposed to establishing an educational institution like a European university in the Land of Israel. He believed that a university that was completely Jewish, serving the Jewish nation, should be established. In 1907, in a letter he published in the "Hapoel Hatzair" newspaper, he even proposed a curriculum for a Jewish university. A year later, he donated his entire library, which was one of the largest Hebrew libraries in the world, to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, which was still in the process of being established.

He frequently wrote letters to "Hapoel Hatzair," "Hashiloach," and other periodicals. One of his well-known essays, "The Ethical State," was published in "Hashiloach" and presented his idea of the purpose of the Jewish state as being primarily ethical. In it, he states that he supported Herzl's political activities, even though he was against them in principle because they aimed at physical well-being. However, Herzl's mission was to create the Jewish state, while Achad Ha'am was concerned with the question of what the state would be like when it was established.

While living in London, he published a collection of his writings in "Al Parashat Derachim," which contained articles he had written between 1889 and 1898, and "Kapaiim," a collection of his poems.

Legacy

Achad Ha'am's ideas had a significant influence on the Zionist movement, particularly in shaping the concept of cultural and spiritual Zionism. He emphasized the importance of Jewish culture and education as a means of preserving Jewish identity and believed that the Land of Israel should be the center of this cultural renewal.

Although his views often clashed with those of other prominent Zionist leaders like Theodor Herzl, who focused more on political and territorial aspects of Zionism, Achad Ha'am's ideas continue to resonate with many who see the cultural and spiritual dimensions of Jewish identity as central to the Zionist project.

Achad Ha'am's legacy can be seen in the continued emphasis on Hebrew language and culture in Israel, as well as in the ongoing debate over the nature and purpose of the Jewish state. His writings and ideas remain an important part of the intellectual history of Zionism and continue to be studied and discussed by scholars and thinkers today.