מורשת גדולי האומה

בזכותם קיים

beta

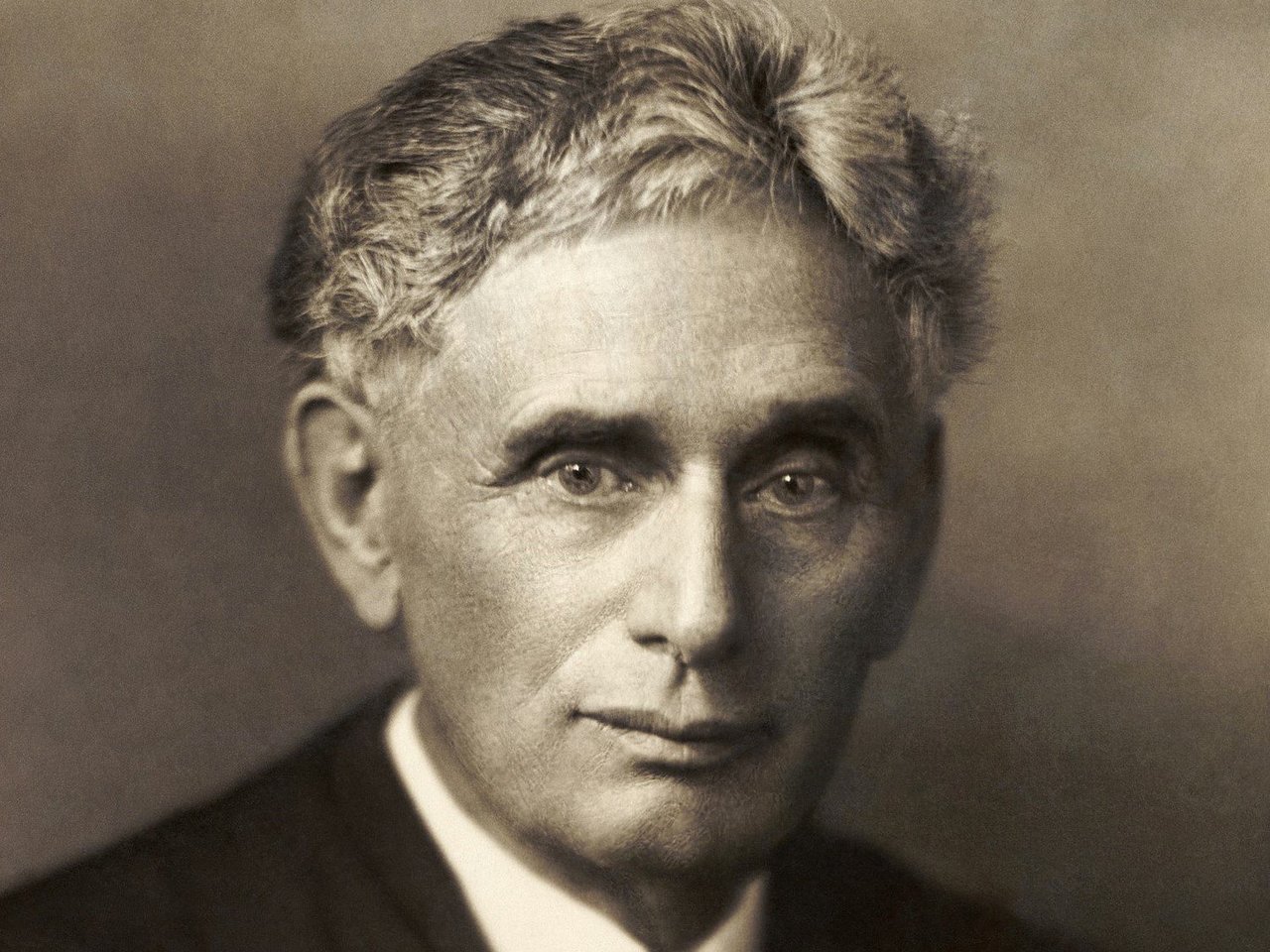

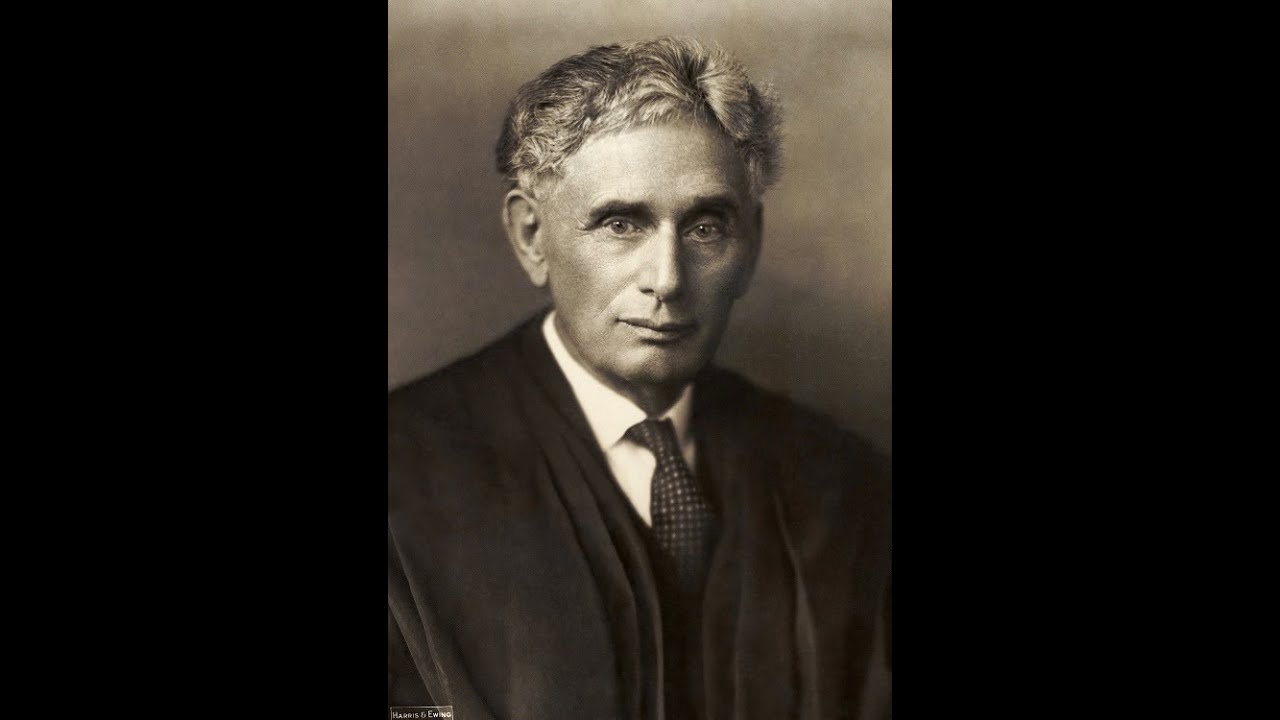

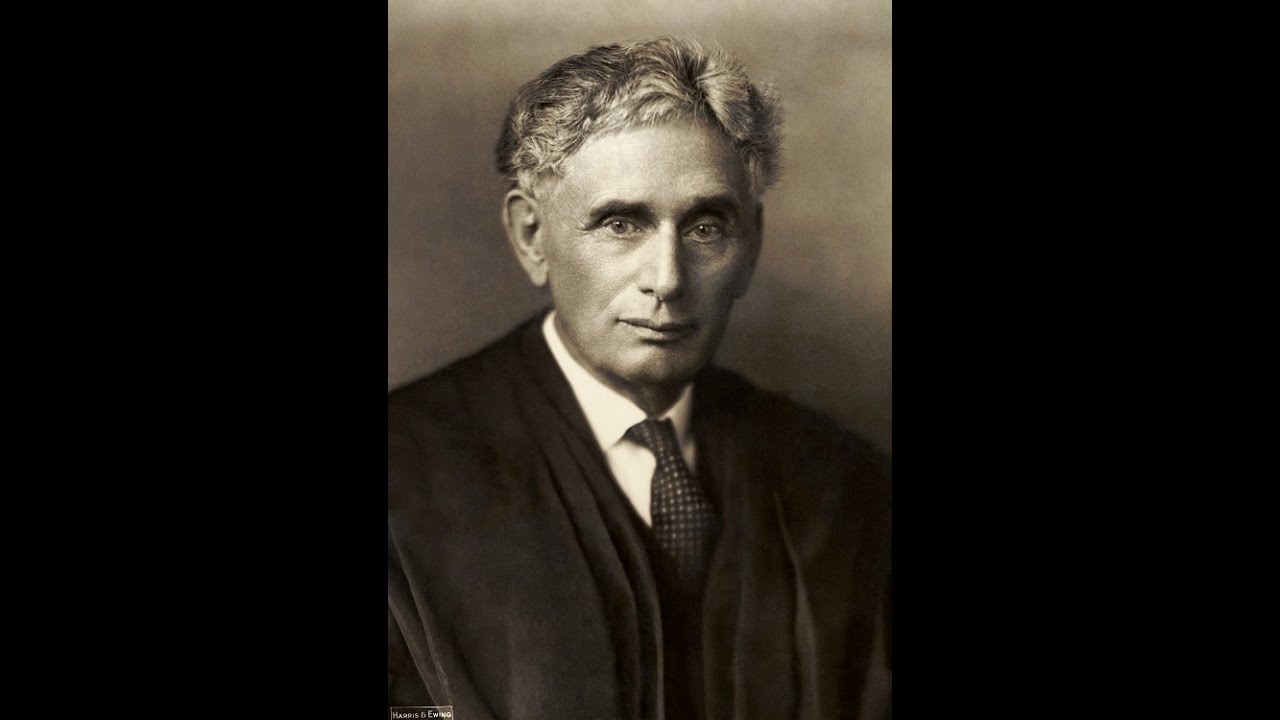

Louis Dembitz Brandeis: A Pioneer in American Jurisprudence

Louis Dembitz Brandeis, with his brilliant legal mind and unwavering commitment to justice, made an indelible mark on American law and society. He was a tireless advocate for consumer rights, labor, and individual privacy. His legacy continues to influence the legal profession and remains a source of inspiration for those who champion the protection of civil liberties and social justice in the United States.

Louis Dembitz Brandeis, born on November 13, 1856, and passing away on October 5, 1941, was a distinguished Jewish-American lawyer and a justice of the United States Supreme Court. Beyond his legal career, he was a fervent Zionist and a leader in the American Zionist movement, playing a pivotal role in the early days of Zionist activism in the United States.

Brandeis was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to parents Adolph Brandeis and Frederika Dembitz, both from prominent Jewish families with roots in Prague. His grandfather and great-grandfather were prominent leaders in their community, fervent supporters of the prophet Reizl Igger. Brandeis was the youngest of four children, and part of his education took place in Dresden when his father encountered financial difficulties and returned to Europe for a period.

Although Brandeis did not receive formal Jewish education, the profound influence of his uncle, Louis N. Dembitz, facilitated his Jewish upbringing. In honor of his uncle, Brandeis adopted the surname "Dembitz" and changed his middle name from David to Dembitz. This uncle, an attorney himself, also nurtured Brandeis's interest in law.

Brandeis's exceptional intellectual abilities were evident during his time at Harvard University, where he achieved remarkable academic success. He became a member of Phi Beta Kappa honor society, and his average score was 97, a record-breaking achievement in the history of Harvard Law School. Completing his degree at the age of 20, which was unusually young, Brandeis rapidly gained recognition as a successful young lawyer in Louisville and later in Boston.

In 1891, at the age of 34, he married Alice Goldmark, his second cousin. The couple had two daughters, Susan Brandeis Gilbert (1893) and Elizabeth Brandeis Rauschenbush (1896).

Brandeis emerged as a champion of consumer rights and labor organizations. He had a significant impact on the opening of the life insurance market and advocated for the regulation of monopolies in the transportation and utility industries in the Boston area. He frequently volunteered for important cases.

In 1908, Brandeis gained widespread recognition for his work in the Muller v. Oregon case. He used empirical evidence to demonstrate the adverse effects of long working hours on women, setting a pioneering example of the legal application of social science knowledge. This case left a lasting mark on the legal profession and became the cornerstone of the "Brandeis brief" and future legal arguments.

His contributions were instrumental in the transformation of American jurisprudence, shifting away from absolute corporate freedom, advocating for fair competition, and improved working conditions. He earned the nickname "The People's Attorney."

Despite his accomplishments, Brandeis faced staunch opposition, with adversaries who sought to block his appointment as an adviser on trade matters in President Woodrow Wilson's cabinet. However, they were unable to dissuade the President from nominating him as a Supreme Court Justice. Wilson announced Brandeis's appointment on January 28, 1916, and after heated debates, the Senate confirmed his nomination on June 1 with a vote of 47 to 22. Brandeis became the first Jewish Justice to serve on the United States Supreme Court.

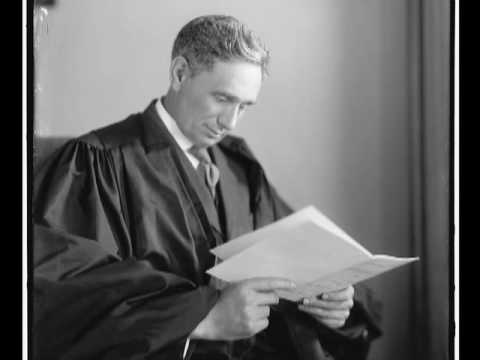

As a Supreme Court Justice, Brandeis continued to uphold his liberal principles and openness to social legislation. He often sided with minority opinions, supporting laws that restricted child labor, among other issues. Alongside his friend Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, he argued that freedom of expression should only be restricted in cases of clear and immediate danger.

In a groundbreaking 1890 article co-authored with Samuel Warren, Brandeis discussed the right to privacy in the context of the emerging field of photography in newspapers. He vehemently opposed wiretapping that allowed eavesdropping on private telephone conversations to catch bootleggers. Brandeis cautioned that technological capabilities to invade individual privacy would grow, and a crime remained a crime, even if committed by the government. However, he concurred with Justice Holmes that some outliers could be exempted. One of his famous quotes, often cited, was on "the right most valued by civilized men - the right to be left alone," which later evolved into a fundamental right to privacy in legal jurisprudence.

Early Life

Brandeis was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to parents Adolph Brandeis and Frederika Dembitz, both from prominent Jewish families with roots in Prague. His grandfather and great-grandfather were prominent leaders in their community, fervent supporters of the prophet Reizl Igger. Brandeis was the youngest of four children, and part of his education took place in Dresden when his father encountered financial difficulties and returned to Europe for a period.

Although Brandeis did not receive formal Jewish education, the profound influence of his uncle, Louis N. Dembitz, facilitated his Jewish upbringing. In honor of his uncle, Brandeis adopted the surname "Dembitz" and changed his middle name from David to Dembitz. This uncle, an attorney himself, also nurtured Brandeis's interest in law.

Brandeis's exceptional intellectual abilities were evident during his time at Harvard University, where he achieved remarkable academic success. He became a member of Phi Beta Kappa honor society, and his average score was 97, a record-breaking achievement in the history of Harvard Law School. Completing his degree at the age of 20, which was unusually young, Brandeis rapidly gained recognition as a successful young lawyer in Louisville and later in Boston.

In 1891, at the age of 34, he married Alice Goldmark, his second cousin. The couple had two daughters, Susan Brandeis Gilbert (1893) and Elizabeth Brandeis Rauschenbush (1896).

Brandeis as a Legal Advocate

Brandeis emerged as a champion of consumer rights and labor organizations. He had a significant impact on the opening of the life insurance market and advocated for the regulation of monopolies in the transportation and utility industries in the Boston area. He frequently volunteered for important cases.

In 1908, Brandeis gained widespread recognition for his work in the Muller v. Oregon case. He used empirical evidence to demonstrate the adverse effects of long working hours on women, setting a pioneering example of the legal application of social science knowledge. This case left a lasting mark on the legal profession and became the cornerstone of the "Brandeis brief" and future legal arguments.

His contributions were instrumental in the transformation of American jurisprudence, shifting away from absolute corporate freedom, advocating for fair competition, and improved working conditions. He earned the nickname "The People's Attorney."

Despite his accomplishments, Brandeis faced staunch opposition, with adversaries who sought to block his appointment as an adviser on trade matters in President Woodrow Wilson's cabinet. However, they were unable to dissuade the President from nominating him as a Supreme Court Justice. Wilson announced Brandeis's appointment on January 28, 1916, and after heated debates, the Senate confirmed his nomination on June 1 with a vote of 47 to 22. Brandeis became the first Jewish Justice to serve on the United States Supreme Court.

As a Supreme Court Justice, Brandeis continued to uphold his liberal principles and openness to social legislation. He often sided with minority opinions, supporting laws that restricted child labor, among other issues. Alongside his friend Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, he argued that freedom of expression should only be restricted in cases of clear and immediate danger.

In a groundbreaking 1890 article co-authored with Samuel Warren, Brandeis discussed the right to privacy in the context of the emerging field of photography in newspapers. He vehemently opposed wiretapping that allowed eavesdropping on private telephone conversations to catch bootleggers. Brandeis cautioned that technological capabilities to invade individual privacy would grow, and a crime remained a crime, even if committed by the government. However, he concurred with Justice Holmes that some outliers could be exempted. One of his famous quotes, often cited, was on "the right most valued by civilized men - the right to be left alone," which later evolved into a fundamental right to privacy in legal jurisprudence.

- לואי ברנדייסhe.wikipedia.org