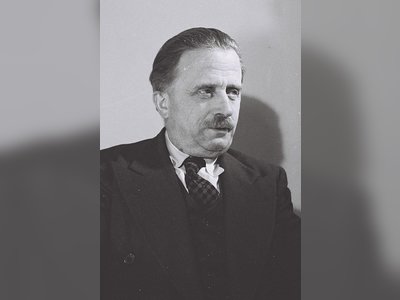

Dr. Israel Rudolf (Rezhe) Kasztner

Israel Kasztner's role during the Holocaust remains a topic of controversy and debate. Some view him as a hero who did his best to save Hungarian Jews, while others accuse him of collaborating with the Nazis. Regardless of one's perspective, his actions and the Kasztner Trial continue to be significant chapters in Holocaust history.

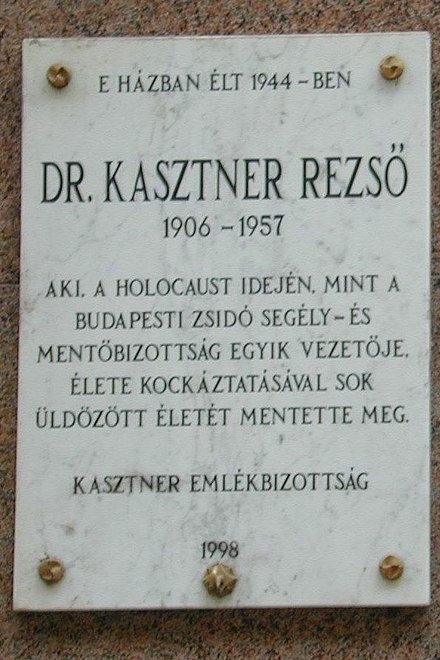

Dr. Israel Rudolf (Rezhe) Kasztner was a lawyer, journalist, and political activist who was a member of the Rescue and Aid Committee in Budapest during the Holocaust. He organized various rescue operations, including the famous "Kasztner Train." He was assassinated in Tel Aviv after being accused of collaboration with the Nazis.

In 1952, Jerusalem-based journalist Malchiel Gruenwald published an article accusing Kasztner of collaborating with the Nazi regime during World War II. The government's legal advisor, Chaim Cohen, filed an indictment against Gruenwald for libel. Gruenwald's trial, which garnered significant public interest, led to a wide-ranging investigation into the Holocaust in Hungary and Kasztner's activities during that time.

It became known as the "Kasztner Trial." In June 1955, the District Court acquitted Gruenwald of most charges, and the judge, Benjamin Halevi, wrote in his verdict that "Kasztner sold his soul to the devil." Following the trial, Kasztner was assassinated in Tel Aviv.

The state later retracted its position, and the Supreme Court's verdict, given after the assassination, concluded that Kasztner did not collaborate with the Nazis and was not involved in the murder of Hungarian Jews or in looting with the Nazis.

However, it was unanimously agreed that "Kasztner rescued, through deceit, iniquity, and cunning, Nazi war criminal Kurt Becher from the death penalty he expected at Nuremberg." Judge Shimon Agranat wrote in his judgment that "history, not the court, should judge Kasztner."

Early Life and Education:

Israel Kasztner was born in 1906 in Cluj (Kluzh), Transylvania, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. He was born into a religious Jewish family, one of three children of Helena and Yitzhak. His mother ran the family store. Kasztner attended a gymnasium and learned to speak seven languages by the time he finished his studies.

At the age of 15, he joined a Zionist youth movement and later became its leader in his city. Kasztner was initially rejected from studying law at the university due to quotas, but he later gained admission to a law school in his hometown and earned a doctorate in law.

Career in Journalism and Politics:

Starting in 1925, Kasztner worked as a journalist for the Hungarian-language Jewish newspaper "Új Kelet" (New East) in Cluj, initially as a sports writer and later as a political journalist. He even interviewed members of the anti-Semitic Iron Guard. From 1929 to 1931, he served as the newspaper's political editor in Bucharest and was part of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency's Romanian office. He was also active in the Zionist youth movement in Transylvania and the Zionist Labor Movement. Kasztner served as the secretary of the parliamentary faction of the Jewish Party in the Romanian Parliament.

Kasztner's Role in Rescuing Hungarian Jews during the Holocaust:

Starting in 1941, Kasztner worked to establish an organization composed of liberal and social-democratic Jews to help Jewish refugees arriving in Hungary. In 1943, this organization became known as the "Rescue and Aid Committee in Budapest."

Otto Komoly served as its chairman, with Kasztner as his deputy and de facto leader of the committee. The committee maintained connections with the Slovakian Working Group and with emissaries from the Yishuv, who were based in Istanbul, Turkey, geographically close to German-occupied territories. Through these connections, the committee learned about the Holocaust in Poland and Russia.

This knowledge was reinforced as Jewish refugees began arriving in Hungary, and through reports from Hungarian army personnel who served in units that participated in the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union.

According to Eli Rekentál, who wrote his doctoral thesis on Kasztner in 2009 and later expanded on the subject in a book, Kasztner was an informant for the Nazis. During the trial, Kasztner denied any contact with Nazi intelligence officer Joseph Adolf Urban. However, after the war, Eli Wiesel interviewed Felix Kersten, Heinrich Himmler's personal physician, who claimed that Kasztner had worked as an informant for him. Wiesel believed that Kasztner was telling the truth. Wiesel sent registered letters to Kasztner, asking if he knew about Urban's actions against Hungarian Jews and urging him to testify. Kasztner did not respond to the letters, claiming he was too busy.

In October 1943, Oscar Schindler met with Kasztner and Samuel Springmann and provided them with a detailed report on the extermination in Poland, particularly in Auschwitz. After the war, Kasztner reported this meeting but omitted the mention of Auschwitz.

Kasztner's actions were met with mixed opinions. Some accused him of not doing enough, while others argued that he did what he could given the circumstances. Professor Yehuda Bauer claimed that Kasztner suggested the establishment of a ministry to warn rural communities not to board the trains to Auschwitz. However, local Jewish councils refused to comply, even though they had received information about the Nazi extermination policy, partly from BBC broadcasts and information from thousands of Jews who had escaped from Poland to Hungary and other sources.

Bauer believed that most Hungarian Jews did not know what awaited them, even when they were boarding the trains. The Jewish leadership was convinced that Hungarian elites would not abandon them, and the public relied on their leaders and trusted their judgment.

Kasztner himself believed that he had breached the victims' trust by not informing them of their fate, which might have saved their dignity, even if not their lives. Therefore, it can be inferred that if a credible leader like Kasztner had warned them, many lives could have been saved.

However, according to Eli Rekentál, the majority of Hungarian Jews did not know what awaited them, even when they boarded the trains. The leadership was convinced that Hungarian elites would not abandon them, and the public relied on their leaders and trusted their judgment.

Kasztner believed that he had betrayed the victims' trust by not informing them of their fate, which might have saved their dignity, even if not their lives. Therefore, it can be inferred that if a credible leader like Kasztner had warned them, many lives could have been saved.

- ישראל קסטנרhe.wikipedia.org