Shabbetai Zvi

Shabbetai Zvi (born 9th of Av, 1626 – passed away 10th of Tishrei, 1676) was a Jewish native of Izmir, often regarded as the most famous false messiah in Jewish history. His influence gave rise to the Sabbatean movement, which swept across the Jewish world for several years, particularly during the 17th and 18th centuries, and its impact is still felt today.

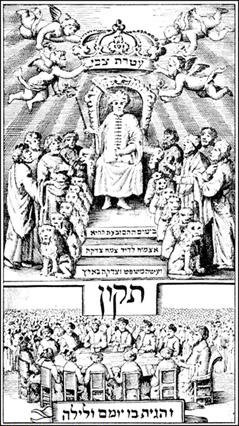

Shabbetai Zvi, born in Izmir, delved into mysticism and Kabbalah from a young age, and he developed a bold claim that he was the Messiah. As he traveled the world, he garnered many followers and believers. During this period, he instituted new religious regulations, abolished traditional customs, and even appointed his own "kings."

In 1666, Shabbetai Zvi was arrested by the Ottoman authorities following accusations made by a Kabbalist named Nehemiah Cohen. He was given the choice between converting to Islam or facing death. He chose to convert, taking the name Aziz Muhammad Efendi, and subsequently, some of his followers also converted. This shocking turn of events sent shockwaves through the Jewish world.

Many believed that his followers had been saved from the massacres that occurred during the Chmielnicki Uprising of 1648-1649, where approximately one hundred thousand Jews were killed in Eastern Europe. Consequently, when Shabbetai Zvi converted, it caused a major crisis among Jews from Turkey and Italy to Russia and Lithuania. In the aftermath, restrictions were imposed on Kabbalah study in Eastern Europe, and Shabbetai Zvi's name became a term of disgrace. He passed away in exile in Ulcinj, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire and is now in Montenegro, at the age of fifty.

Early Life

Shabbetai Zvi was born in Izmir (or the nearby town of Tire) on the 9th of Av, 1626. He was the second son of Mordechai Zvi, a poultry and egg merchant, likely of Romaniote origin, who became a representative for European merchants. His name, Shabbetai, was given to him in accordance with the tradition of naming a child born on the Sabbath "Shabbetai."

In his youth, Shabbetai studied under the rabbis of Izmir, Rabbi Joseph Escapa and Rabbi Isaac Di Alba. He received the title "sage" from Rabbi Joseph Escapa and was recognized as a scholar among the rabbis of Izmir. By the time he reached his twenties, Shabbetai began to withdraw from public life, immersing himself in mysticism and Kabbalah. He also engaged in various unconventional practices. In his early twenties, he married twice but eventually divorced both wives as he did not maintain relations with them. Many in Izmir attributed his behavior to a dual personality disorder.

It appears that during his Kabbalistic studies, Shabbetai did not engage with the works of Isaac Luria (the Ari) that were popular among Kabbalists at the time. Instead, he delved deeply into earlier Kabbalistic texts like the Zohar and the writings of the Kannei and Peliyah. Shabbetai opposed the acceptance of the Ari's teachings and their widespread study among Kabbalists, focusing instead on older Kabbalistic literature.

He developed an extreme Kabbalistic doctrine that posited the existence of two separate divine entities and justified certain violations of Jewish law as necessary for the world's rectification. Shabbetai knew that his Kabbalistic doctrine would not be well-received by the rabbis of his time, so for years, he only taught it to his closest disciples.

On the 21st of Sivan in 1648, after the outbreak of the Chmielnicki Uprising and the massacres in Ukraine, Shabbetai had a major breakthrough. In a vision, he believed he was revealed as the Messiah. He did not hesitate to publicize his vision, and he began to adopt unusual practices openly, including pronouncing the explicit name of God as it is written in the Torah, despite the halachic prohibition.

He justified this by arguing that in the days of the Messiah, the explicit name of God would be pronounced differently than it is today (in the form of the tetragrammaton, YHWH). Shabbetai believed he was the Messiah and that the time had come to pronounce the name of God as written. His actions shocked the Jewish world, and many of his followers believed they were survivors of the recent massacres because of his revelation.

As a result, when Shabbetai was apprehended and converted to Islam, it led to a major crisis among Jews from Turkey and Italy to Russia and Lithuania. The event also prompted restrictions on Kabbalah study in Eastern Europe, and the name Shabbetai Zvi became synonymous with disgrace. Shabbetai passed away in exile in Ulcinj, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire and is now in Montenegro, at the age of fifty.

Early Wanderings

After his conversion, Shabbetai Zvi initially traveled to Salonika, where he gained many new disciples and followers. However, even in Salonika, he could not refrain from his unconventional behaviors. On one occasion, he arranged a mock wedding ceremony for himself, with the bride being a Torah scroll, symbolizing his messianic identity as the "husband" of the Torah. This stirred controversy in Salonika, and Shabbetai attempted to justify it using Kabbalistic explanations. Nevertheless, Salonika expelled him after this incident.

Shabbetai then embarked on a series of wanderings through Greek cities, continuing his unorthodox practices and studying Kabbalah. Despite his earlier marriage, he attempted another unconventional marriage ceremony in Salonika, declaring that every Jewish person was considered the spouse of the Torah, as part of his messianic beliefs. This act created a major uproar in Salonika, and rabbis in the city, including his teacher Rabbi Joseph Escapa, began persecuting him in an effort to force him to leave.

Between 1651 and 1654, Shabbetai Zvi was expelled from Izmir, and he continued his wanderings in Greek cities, eventually reaching Kushta (Kuşadası) in 1658, accompanied by a congregation of his devoted followers. In Kushta, he performed public acts of extravagance, such as wandering the streets with a giant fish in a baby's cradle and offering mystical interpretations for his actions.

He celebrated all three pilgrimage festivals in one day, part of his strategy to confound traditional dates, and he conducted a Seder on Sukkot, incorporating Kabbalistic elements. During this time, he also introduced a unique blessing during morning prayers, "Baruch Matir Asurim," inspired by a Midrashic interpretation that suggested that in the Messianic era, prohibitions would be lifted.

Shabbetai Zvi believed that since he was the Messiah, it was the appropriate time to pronounce this blessing. The date of the 21st of Sivan, when Shabbetai Zvi "revealed" himself, became a day of celebration among his followers, known as "Yom Hachana" (the Day of Preparation). It was observed with fasting and prayers in anticipation of the Messianic era.

Shabbetai's charismatic and controversial actions gained him a considerable following, even as he continued to roam from city to city. He claimed that he was the true Messiah and that his mission was to liberate the Jewish people from oppression and exile. As his movement grew, it attracted not only Jews but also non-Jews who were drawn to his charismatic personality and his vision of a utopian future.

Excommunication and Imprisonment

As Shabbetai Zvi's influence grew, so did the opposition from rabbinical authorities. Many rabbis regarded his messianic claims and behavior as heretical and disruptive to Jewish tradition. Some of the rabbis who opposed Shabbetai included Rabbi Jacob Sasportas and Rabbi Moses Galante, both of whom authored works critiquing his movement.

In 1665, a significant portion of the Jewish world came to a consensus and issued a ban of excommunication, or "cherem," against Shabbetai Zvi and his followers. The excommunication was led by Rabbi Jacob Sasportas and Rabbi Moses Galante and was supported by a broad coalition of rabbis from various Jewish communities.

The excommunication had a dual purpose: first, to denounce Shabbetai Zvi as a false messiah and to protect Jewish tradition from his radical interpretations, and second, to pressure him into recanting his messianic claims. However, the ban had limited impact on Shabbetai and his followers, who regarded it as a test of faith and continued to follow him.

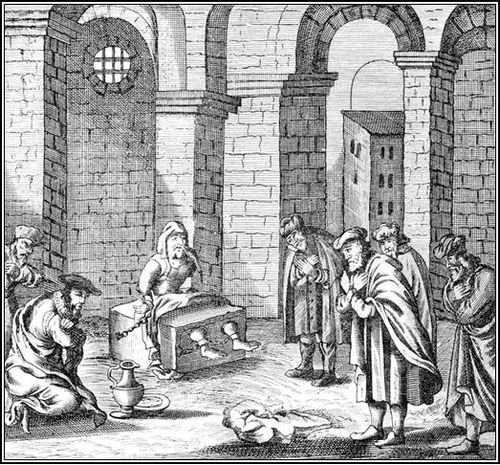

In 1666, Shabbetai Zvi made a bold move by traveling to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) with the intention of meeting the sultan, Mehmed IV. It is believed that he hoped to gain the sultan's support and protection for his messianic mission. However, the authorities in Constantinople arrested Shabbetai Zvi on charges of sedition and heresy. He was imprisoned for several weeks while awaiting trial. During this time, he faced intense scrutiny from rabbis and other Jewish leaders who had come to confront him and demand that he renounce his messianic claims.

Conversion to Islam

In September 1666, Shabbetai Zvi's life took a dramatic turn. Faced with the choice of execution or conversion to Islam, he chose the latter. On the 15th of Elul, he publicly embraced Islam and took the name Aziz Muhammad Efendi. This decision stunned his followers and the Jewish world at large. Many of his followers were devastated and confused by the sudden turn of events. The fact that their messianic leader had converted to Islam was a severe blow to the Sabbatean movement.

Shabbetai's conversion was a complex and controversial matter. Some interpretations suggest that he may have believed that his messianic mission could continue in some form within Islam, possibly as a mystical redeemer. Others speculate that he may have feigned conversion to save his life or that he suffered from mental illness. The exact reasons behind his conversion remain a subject of debate among historians and scholars.

Following his conversion, Shabbetai Zvi was placed under the supervision of various Ottoman authorities. He lived in different locations within the Ottoman Empire, including Constantinople and the city of Adrianople (modern-day Edirne, Turkey). During this period, he continued to attract followers, albeit on a smaller scale, among both Jews and Muslims.

Legacy and Impact

The conversion of Shabbetai Zvi to Islam marked the dramatic end of his messianic movement, but it did not extinguish the influence of his ideas and the memory of his charismatic leadership. While the majority of his Jewish followers did not convert to Islam, some did, forming a small group known as the "Dönmeh." This group continued to exist in secrecy and practiced a form of crypto-Judaism combined with elements of Islamic mysticism.

In the years following Shabbetai Zvi's conversion, his story continued to be a source of fascination and debate within Jewish communities. The Sabbatean movement, in various forms, persisted for generations and had a lasting impact on Jewish history. Some remnants of Sabbatean beliefs and practices can still be found in certain Jewish communities today.

Shabbetai Zvi's life and the rise and fall of his messianic movement have been the subject of numerous books, scholarly studies, and cultural works. His story has inspired novels, plays, and even operas. He remains one of the most enigmatic and controversial figures in Jewish history, a charismatic leader whose messianic claims shook the Jewish world and left a lasting legacy that continues to be explored and debated to this day.

- שבתי צביhe.wikipedia.org