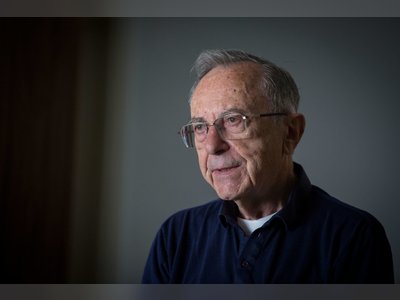

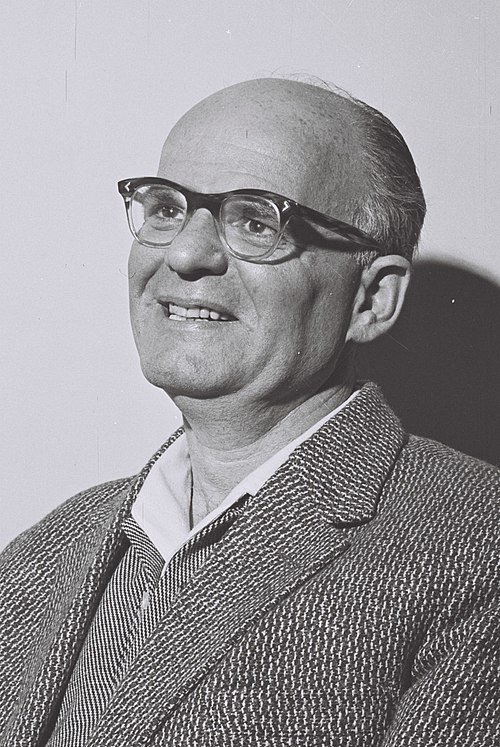

Yura Josephthal : A Life of Zionist Dedication and Public Service

Yura Josephthal, born Georg Josephthal, was a prominent figure in the Zionist movement in Germany and later served as a minister in the government of Israel. His life journey is marked by his commitment to Jewish causes, from his early involvement in youth organizations to his significant contributions to the Jewish Agency and the State of Israel.

Early Life and Youth

Born on August 9, 1912, in Nuremberg, Germany, Yura Josephthal was the fourth child of Paula and Emil, a metal factory manager and a World War I veteran who had received a bravery award. His grandfather, Gustav Josephthal, was a lawyer, head of the local bar association, and a leader in the local Jewish community in Nuremberg.

At the age of 14, while still a student at a gymnasium in Nuremberg, he joined the Jewish youth association "Jüdischer Jugendbund" (Jewish Youth League). He completed his secondary education at a humanistic gymnasium in 1930.

Zionist Activism

Josephthal began studying law at Heidelberg with the intention of joining the family law firm. In 1932, he joined the Zionist-socialist youth movement "Hashomer Hatzair" (The Young Guard). During his studies in Berlin and Munich, he volunteered for various tasks within the Jewish community.

He organized vocational training workshops and agricultural training for young Jewish people, preparing them for immigration to Palestine. In 1933, with the rise of the Nazis to power, he continued his studies in Basel, Switzerland, where he completed his doctorate in law.

In 1934, he moved to Berlin and became the director of youth immigration. In early 1936, he was appointed as the general secretary of "HaHalutz" (The Pioneer), the youth organization of the Jewish community in Germany. During his time there, he established training centers for professional skills and agricultural training for the youth, equipping them for their future lives in Palestine.

In 1937, when the Nazis confiscated one of the hidden weapons caches, which included a photo of Josephthal, he was briefly arrested but released due to lack of evidence. His good relationships with local authorities played a role in securing his release.

In September 1938, Josephthal and his wife, Santa, immigrated to Palestine and settled in Kibbutz Givat Haim. Shortly after the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938, he was sent on a mission to London to work towards the rescue of German Jews.

He organized escape routes through Rotterdam and Antwerp and prepared ships for immigration. In the spring of 1939, Josephthal was arrested in Paris, where he was found in possession of forged documents.

Due to his influential connections, he was eventually released. The outbreak of World War II led to the end of this escape route operation, and he returned to Palestine by the end of that year.

From January 1943 until September 1945, he volunteered to serve in the British Army and was stationed in Israel and Egypt, achieving the rank of sergeant but being demoted due to his refusal of orders. His wife, Santa, joined a nucleus of German-Jewish immigrants and established Kibbutz Geva, while Josephthal resumed his service there briefly upon his release from the British Army.

Involvement with the Jewish Agency

In the autumn of 1945, Josephthal began his work with the Jewish Agency and served as the head of the immigration department.

Two years later, in 1947, he was appointed as a member of the Jewish Agency's executive committee, and prior to that, he served as the head of the immigration department during a period of mass immigration until 1956.

Josephthal perceived the cultural differences among Eastern and North African immigrants as a challenge to the integration of various groups and advocated for changes in the way these newcomers were received.

He believed that the world was changing, and the lifestyle of these immigrants needed to adapt to modern norms. He stated his position during the 23rd Zionist Congress in 1951:

"The fundamental conditions for the integration of immigrants are changes in the way of life of the immigrants from backward countries. One way to achieve this is by supporting the weak and marginalized within the family - the child and the woman.

There is nothing in common between parents who provide everything for their children and regard education and health care as essential to their well-being, and those who deprive their children of their meals and wrap them in blankets meant for their infants, sending their children to work at a young age without understanding the concept of education or knowing what a doctor and medicine are.

Integration cannot happen if, in one family, women are sent to work a few days after giving birth while, in another family, the last drop of milk is spared to ensure help for the new mother.

Integration will not occur through words alone but through education and care, rooted in changes in lifestyle, preserving the right to life for the weak, abolishing the power of the patriarch, and eliminating the free reign of men."

To bring about this cultural change, Josephthal focused on educational programs for children and youth, as well as vocational training and education for women. He also supported a shift in the immigration policy from mass immigration to selective immigration, citing his concerns about immigrants from North Africa, stating that they were "unfit" and lacked a future.

When protests erupted at immigrant camps following harsh conditions during the winter of 1951, Josephthal blamed the Eastern immigrants for their passivity and reluctance to help themselves.

In 1952, he even proposed making Eastern European immigrants sign commitments to settle in designated locations before their arrival. He said, "This is bureaucracy versus primitive people.

Their signatures have no value; these people have no understanding of what they are signing." In 1951, when immigrants from North Africa rioted in transit camps due to a perceived lack of support, Josephthal suggested using a legal loophole to accuse parents of neglecting their children and threatened to involve the police to take the children by force if needed.

In addition to his work with immigrants, he was instrumental in creating legislation to protect disabled and handicapped workers. He also advocated for improving vocational training and education for the youth.

Political Career

In August 1956, with the support of David Ben-Gurion, Josephthal was appointed as the Secretary-General of the Israeli Labor Party (Mapai), and he was tasked with reforming the party following significant losses in elections. However, he found the role ill-suited to his personality and was not successful in implementing significant reforms. In May 1959, Josephthal suffered a severe heart attack, which forced him to take a six-month hiatus from his work.

Josephthal served as a member of the Knesset (Israeli Parliament) on behalf of Mapai during the 4th and 5th Knessets from 1959 to 1962. In December 1959, he entered the Knesset and began his service as Minister of Labor in 1960.

During his brief tenure in the Knesset, he focused on vocational training for youth and new immigrants, the development of national insurance, and championed a law to protect disabled and handicapped workers. In November 1961, following David Ben-Gurion's resignation and the subsequent elections for the leadership of Mapai, Josephthal expressed his support for Levi Eshkol's candidacy for Prime Minister.

Legacy

Yura Josephthal's life was marked by his unwavering dedication to Zionist causes, particularly the immigration and integration of Jewish refugees into Palestine and later Israel. His efforts in the Jewish Agency and the Israeli government aimed at shaping policies that would help immigrants adapt to their new home. However, some of his approaches were criticized for being heavy-handed and paternalistic, particularly in his dealings with immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East.

Josephthal's sudden death on August 23, 1962, at the age of 50, cut short what could have been a longer and more influential political career. Despite the controversies surrounding his methods, he remains a notable figure in the history of Zionism and the early years of the State of Israel, remembered for his passionate commitment to the Jewish people and their homeland.

- גיורא יוספטלhe.wikipedia.org